As I mentioned just over a month ago, I recently finished book #600—the 600th book, that is, since I began tracking my reading back in June of 2015. When I announced this milestone at the very cusp of the new year, I had only barely finished my analysis of the 5th hundred books read. I will (I hope) get around to such an analysis for this 6th hundred set of books, but here and now I merely want to present you with the listing of all the books which make up this latest set, Books #501 through #600. As is usual, I do not include comics and graphic novels as ‘books’ in my count, though they are listed below.

The 600th book I’ve read is the history of the early medieval era depicted at the top of this post, about which I wrote some brief notes in the original announcement of reaching the reading milestone. The first book in this last set of a hundred books—Book #501 read—is another delightful entry of The Month, notes upon noteworthy acquisitions by the wonderful (and long defunct, alas) Boston bookstore, Goodspeed’s. The particular issue which started off this last century of books was that of September 1931, whose cover is depicted at right. I should also note that I shall have very few links to make to my sometimes ‘book reports’ on this or that volume which come to my hand, as I read at such a ridiculous pace that (with a single exception, covering two books) I did not write at all about any of the books I read. I have to confess that I was endeavoring to read as fast as I possibly could, and thus read quick studies, short books or pamphlets, children’s books, and—especially—mysteries. I still managed to read a few comics, as you shall see in this first slice of ten books. (The renditions of The Mahabharata labeled as ‘Children’s books’ were originally thought by me to be comics as well, but when I read them I realized that they were just (incredibly poorly written and even more poorly proofread) text with a picture for each page, and thus were not comics after all.)

| # |

Read |

Author |

Title |

Genre |

| 501 |

9/13/20 |

Norman Dodge |

The Month at Goodspeed’s Book Shop September 1931, Vol. III No. 1 |

Books |

|

9/14/20 |

Walt Disney |

Le Journal de Mickey No. 1398 bis – Mickey Parade: Tout va bien Donald! |

Comics |

| 502 |

9/14/20 |

Norman Dodge |

The Month at Goodspeed’s Book Shop July 1930, Vol. I No. 10 |

Books |

| 503 |

9/15/20 |

Curtis F. Brown |

Star-Spangled Kitsch |

Art |

| 504 |

9/16/20 |

Erle Stanley Gardner (as A. A. Fair) |

Spill The Jackpot |

Mystery |

| 505 |

9/16/20 |

Norman Dodge |

The Month at Goodspeed’s Book Shop October 1930, Vol. II No. 2 |

Books |

| 506 |

9/17/20 |

Agatha Christie |

The Labors Of Hercules |

Mystery |

|

9/17/20 |

B. R. Bhagwat, trans. |

Mahabharata |

Comics |

|

9/17/20 |

Kamala Chandrakant |

Mahabharata – 13: The Pandavas Recalled to Hastinapura |

Comics |

|

9/17/20 |

Milami |

Mahabharata – 20: Arjuna’s Quest for Weapons |

Comics |

|

9/17/20 |

Sumona Roy |

Mahabharata – 22: The Reunion |

Comics |

|

9/17/20 |

Sumona Roy |

Mahabharata – 26: Panic in the Kaurava Camp |

Comics |

|

9/17/20 |

Sumona Roy |

Mahabharata – 27: Sanjay’s Mission |

Comics |

| 507 |

9/18/20 |

Vinay Krishan Saxena |

Mahabharata Part 1 |

Children’s |

| 508 |

9/18/20 |

Vinay Krishan Saxena |

Mahabharata Part 2 |

Children’s |

| 509 |

9/26/20 |

Jonathan Gash |

The Tartan Sell |

Mystery |

| 510 |

9/27/20 |

Military Medical Operations Office |

AFRRI’s Medical Management of Radiological Casualties Handbook |

Militaria |

I read only a couple of good books in the next set of ten books, including this slim volume of Do’s and Don’t’s from one of the masters of linguistic precision. Write It Right was likely a bit dated in its imprecations even when first published, and now some of Ambrose Bierce’s dicta seem like the ravings of a fussbudget grammarian. There are many scintillating jewels of wit, however, and many of the subjective (as Bierce himself admits) rules seem only common sense, hearkening back to an Edenic time when writers sought to communicate rather than obfuscate, and when readers sought understanding rather than confirmation of their prior prejudice.

The other treasure among this next tranche—setting aside for the nonce the always delightful Beatrix Potter, whose illustrations are beautiful in every language—is the Ray Bradbury collection R Is For Rocket, which uses the rocket theme to good effect to present some old favorites and some more unfamiliar masterpieces. I find myself liking Bradbury more as I get older, which may have more to do with the power of nostalgia on the aging mind of mine than on the intrinsic worth of one of America’s premier short story writers. This particular collection was targeted for children—sorry, young readers—and I found somehow the focus on the dreams of the young (an everpresent theme for Bradbury) made reading these poignant stories from the recent century almost painful at times. I cried for my loss, for our loss.

| # |

Read |

Author |

Title |

Genre |

| 511 |

9/27/20 |

Ambrose Bierce |

Write It Right |

Reference |

| 512 |

9/27/20 |

Paul Nettl |

Mozart and Masonry |

Secret Societies |

| 513 |

9/27/20 |

Beatrix Potter; Victorine Ballon & Julienne Profichet, trans. |

Historie de Pierre Lapin |

Foreign Language |

| 514 |

9/28/20 |

Vinay Krishan Saxena |

Mahabharata Part 3 |

Children’s |

| 515 |

9/29/20 |

Vinay Krishan Saxena |

Mahabharata Part 4 |

Children’s |

| 516 |

9/30/20 |

E. E. “Doc” Smith |

First Lensman |

SF & Fantasy |

| 517 |

9/30/20 |

Vinay Krishan Saxena |

Mahabharata Part 5 |

Children’s |

| 518 |

10/1/20 |

Vinay Krishan Saxena |

Mahabharata Part 6 |

Children’s |

| 519 |

10/2/20 |

Ray Bradbury |

R Is For Rocket |

SF & Fantasy |

| 520 |

10/2/20 |

N.K. Vikram |

Shri Krishna Leela Part 1 |

Children’s |

More feeble books awaited my displeasure in the next set of ten, enlivened however by a few choice morsels of what makes reading fun. Fun is the word for the Dray Prescot series, which deserves to be read more widely, though taking it too seriously would entirely miss the point. Krozair of Kregen wraps up the ‘Krozair Cycle’ of the books by the pseudonymous Alan Burt Akers (penance of Kenneth Bulmer when crafting Dray Prescot books), and while it is not my favorite (due in part to Bulmer’s need to pull all the threads of his far-flung narrative back together in the end), it does have one of the best covers, which you can see here. I’ve just finished the Jikaida Cycle, which may be my favorite of the entire series, which is saying something after twenty-two books read.

I actually kept The DAW Science Fiction Reader for the Dray Prescot short story, but almost all of the contributions here (the exceptions are the Stableford and the Tanith Lee stories) are brilliant. The ‘kids’ novella Fur Magic by Andre Norton is a staggering and inventive remix of fantasy and what we nowadays call Native American mythology. Taking up half the book, it is worth the price of admission on its ownsome. (You can also find the story in a standalone edition.)

| # |

Read |

Author |

Title |

Genre |

| 521 |

10/3/20 |

Isaac Asimov |

Nightfall and Other Stories |

SF & Fantasy |

| 522 |

10/3/20 |

N.K. Vikram |

Shri Krishna Leela Part 2 |

Children’s |

| 523 |

10/4/20 |

Agatha Christie |

Passenger To Frankfurt |

Mystery |

| 524 |

10/4/20 |

N.K. Vikram |

Shri Krishna Leela Part 4 |

Children’s |

| 525 |

10/5/20 |

Richard Rohr |

Falling Upward: A Spirituality for the Two Halves of Life |

Feeble |

| 526 |

10/6/20 |

Alan Burt Akers |

Krozair of Kregen (Dray Prescot #14) |

SF & Fantasy |

| 527 |

10/6/20 |

Harry Graham |

Ruthless Rhymes For Heartless Homes |

Humor |

|

10/10/20 |

Craig Yoe, ed. |

Voting Is Your Super Power |

Comics |

| 528 |

10/10/20 |

Donald A. Wollheim, ed. |

The DAW Science Fiction Reader |

SF & Fantasy |

| 529 |

10/11/20 |

Jacob Needleman |

Money and the Meaning of Life |

Philosophy |

| 530 |

10/12/20 |

Francis Leary |

Fire And Morning |

Fiction |

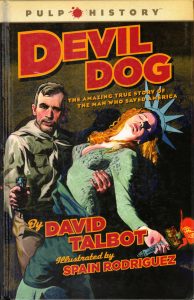

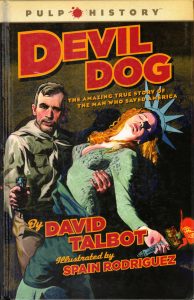

The quality of the books read rose significantly over the next set of ten, as did quite naturally my enjoyment of the same. One of several highlights was this engaging and inspiring retelling of the Smedley Butler story, which every American should know and take to heart. Devil Dog may only go over previously known history, but the breezy retelling by David Talbot accompanied with historical photographs and the art by the fantastic underground comic anarchist artist Spain is a worthy biography for the Marine general who wrote War Is A Racket and who saved America.

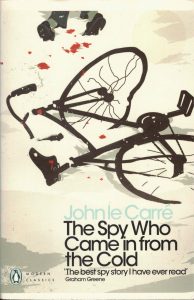

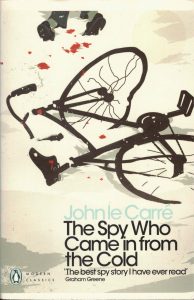

The stunning, brilliant, and engrossing Spy Who Came In From The Cold was only one of the several excellent mysteries and thrillers read in this next slice of ten books. Much has been made before about the revelatory insights of this seminal Cold War novel by the British writer John le Carré, another spy whose assumed name became almost more a reality than the original man. What still staggers after all these years is just how perfectly le Carré hit the mark in this intricate and delicate tale of lies and lying, especially after the perfectly serviceable but somewhat more traditional two novels which came before this addition to the ‘Smiley’ oeuvre. The other spy books read in this set were fun, with Moonraker providing another fantastic high-stakes gambling set piece (taking up fully one third of the book!), but (as usual) Michael Gilbert was the next best read in this set. Average rating for the entire set of ten was a whopping 4.5!

| # |

Read |

Author |

Title |

Genre |

| 531 |

10/12/20 |

Ken Krippene |

Life Among The Amazon |

Nature |

| 532 |

10/12/20 |

Daniel Pinkwater |

Wingman |

Children’s |

| 533 |

10/13/20 |

William Faulkner |

Barn Burning |

Fiction |

| 534 |

10/15/20 |

Ian Fleming |

Moonraker |

Mystery |

| 535 |

10/17/20 |

John le Carré |

The Spy Who Came In From The Cold |

Mystery |

| 536 |

10/18/20 |

Donna Leon |

A Venetian Reckoning |

Mystery |

| 537 |

10/18/20 |

David Talbot; Spain Rodriguez, illus. |

Devil Dog: The Amazing True Story of the Man Who Saved America |

History |

| 538 |

10/20/20 |

Ian Fleming |

Diamonds Are Forever |

Mystery |

| 539 |

10/23/20 |

Melville Davisson Post |

The Sleuth of St. James’s Square |

Mystery |

| 540 |

10/24/20 |

Michael Gilbert |

The Night Of The Twelfth |

Mystery |

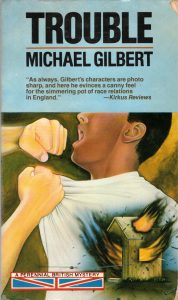

Michael Gilbert continued to thrill in Trouble, an engaging story of community anger and … something more. Perhaps a trifle naïve in its views of race problems, but who am I to judge? The story never lags, however, and Gilbert’s usual deft plotting and characterization keep you guessing right up to the very end. The realistic portrayal of the difficulties in community policing are shown with some sympathy.

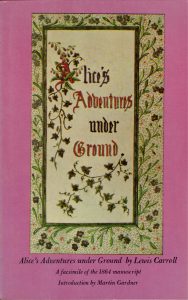

I believe this is the first time I’ve read the ‘original’ version of the Alice story. I am still so impressed by Carroll’s ability to cast his line and hook this best and brightest piece of nonsense from the aether, and even more so upon seeing just how much was there almost right from its inception. Reading Sylvie and Bruno can seem like a chore (because it is), but reading this early version of the classic tale—cringe-inducing postscript aside—is as delightful as the one we all know and love, especially with Lewis Carroll’s earnest illustrations.

| # |

Read |

Author |

Title |

Genre |

| 541 |

10/25/20 |

Alexander Sprunt, Jr. |

Wildlife Refuges |

Nature |

| 542 |

10/25/20 |

James Thurber |

The 13 Clocks |

Fiction |

| 543 |

10/26/20 |

Margaret Frazer |

The Boy’s Tale |

Mystery |

| 544 |

10/28/20 |

Hafiz; Gertrude Bell, trans. |

The Garden of Heaven: Poems of Hafiz |

Poetry |

| 545 |

10/29/20 |

Michael Gilbert |

Trouble |

Mystery |

| 546 |

11/1/20 |

Meg Bogin |

The Women Troubadours |

History |

| 547 |

11/1/20 |

Lester W. Grau |

Rebirth of the Cossack Brotherhood: A Political/Military Force in a Disintegrating Russia |

Militaria |

| 548 |

11/2/20 |

Mikhail Chernenok |

Losing Bet |

Mystery |

| 549 |

11/4/20 |

Lewis Carroll |

Alice’s Adventures Under Ground |

Children’s |

| 550 |

11/4/20 |

James Hadley Chase |

The World In My Pocket |

Mystery |

The true highlight of the next set of ten books read was Thor Heyerdahl’s sequel to Kon-Tiki, the Norse explorer’s now discredited account of eastern migration to the Polynesian islands of the Pacific Ocean. The book, Aku-Aku, is an account of a season spent mostly on Easter Island, investigating how the mysterious statues of that remote outpost may have been constructed. How much truth he may have excavated along with the artifacts he definitely revealed, the book is a breathless account of a people whose ways were already disappearing under the grinding pressure of so-called ‘civilization’.

With Uncle Boris In The Yukon I have the opposite problem of classification. Purporting to be memoir, I am mesmerized by Daniel Pinkwater’s storytelling ability to the extent that I cannot care to speculate upon how much—if any—of his tales are actually true. What is obviously true is Pinkwater’s deep love for dogs of all kinds, though especially for the fearsome and fearless dogs of the Arctic. Any dog lover will love this book.

| # |

Read |

Author |

Title |

Genre |

| 551 |

11/5/20 |

Donna Leon |

Acqua Alta |

Mystery |

| 552 |

11/9/20 |

Cornell Woolrich |

The Black Path Of Fear |

Mystery |

| 553 |

11/10/20 |

Margaret Frazier |

The Murderer’s Tale |

Mystery |

| 554 |

11/11/20 |

Mary Roberts Rinehart |

The Window At The White Cat |

Mystery |

| 555 |

11/12/20 |

Thich Nhat Hanh |

The Heart of Understanding: Commentaries on the Prajnaparamita Heart Sutra |

Spirituality |

| 556 |

11/12/20 |

Thor Heyerdahl |

Aku-Aku |

Antrhopology |

| 557 |

11/15/20 |

U.S. Army Medical Research Institute |

USAMRICD’s Medical Management of Chemical Casualties Handbook |

Militaria |

| 558 |

11/15/20 |

Daniel Pinkwater |

Uncle Boris in the Yukon: and Other Shaggy Dog Stories |

? |

| 559 |

11/15/20 |

Lester Dent |

Honey In His Mouth |

Mystery |

| 560 |

11/16/20 |

Alexander B. Klots |

In The Arctic |

Nature |

|

11/19/20 |

Del Close, John Ostrander |

Wasteland #10 |

Comics |

The next set of ten books was to bring several disappointments, including the kickoff, the once highly touted Freakonomics which once was supposed to be so insightful and revelatory, but which merely seems of a piece with all the ‘life hack’ shit we read on clickbait posts around the Web nowadays. More hurtful to my own psyche was the dreary finale of Mostly Harmless, the fifth and final book in the Hitchhiker’s Guide trilogy. Though it is just as much a downer as everyone says it is, still there are flashes of élan, though Adams is obviously just going through the motions. How hard it is to recapture that first brilliant rapture. It is skippable, if you are so inclined. Listen to the original radio show for the true wonder of our age.

I raved so much just previously about The Spy Who Came In From The Cold that it behooves me to backtrack just a little bit. Not to take away any of the praise I bestowed on that novel, but to proclaim that the first novel of the Smiley series, Call For The Dead, is every bit as excellent, if more of a typical mystery tale. In this our first meeting with George Smiley, the unpresuming bureaucratic spy is more a protagonist, even as the spywork is less central to the novel. All thumbs up!

| # |

Read |

Author |

Title |

Genre |

| 561 |

11/22/20 |

Steven D. Levitt & Stephen J. Dubner |

Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything |

Business |

| 562 |

11/22/20 |

Margaret Frazer |

A Play Of Isaac |

Mystery |

|

11/22/20 |

Luis M. Fernandes |

The Golden Mongoose and other tales from The Mahabharata |

Comics |

| 563 |

11/28/20 |

Edward Topsell |

Elizabethan Zoo: Book of Beasts Both Fabulous and Authentic |

History |

| 564 |

11/29/20 |

Peter Dickinson |

The Old English Peep Show |

Mystery |

| 565 |

11/29/20 |

Norman Dodge |

The Month at Goodspeed’s Book Shop October 1931, Vol. III No. 2 |

Books |

| 566 |

11/30/20 |

Henry Beard, Christopher Cerf, Sarah Durkee, & Sean Kelly |

The Book Of Sequels |

Humor |

| 567 |

12/1/20 |

John Le Carré |

Call For The Dead |

Mystery |

| 568 |

12/3/20 |

Norman Dodge |

The Month at Goodspeed’s Book Shop December 1931, Vol. III No. 4 |

Books |

| 569 |

12/5/20 |

Douglas Adams |

Mostly Harmless |

SF & Fantasy |

| 570 |

12/6/20 |

Norman Dodge |

The Month at Goodspeed’s Book Shop January 1932, Vol. III No. 5 |

Books |

The best of the next ten books includes Madeline (which I had never read before, somehow), along with the Donna Leon and the always wonderful Month at Goodspeed’s. Though the first and last of these are very short reads, they each punch well above their length, and I am quite happy to have perused them.

The worst of this set of ten—and perhaps the worst of the full set of one hundred—was the execrable little pamphlet of pseudo-bullshit from the ’70s, How To Be Your Own Best Friend. I was given this as a present for my eleventh or twelfth birthday, and the message I got was “… because you’re not going to have any other friends.” After reading it now, I don’t think there is an actual message within this book, except perhaps that people will buy anything I guess. It has aged terribly (vide, its references to homosexuality), but it was very terrible to begin with.

| # |

Read |

Author |

Title |

Genre |

| 571 |

12/6/20 |

Mildred Newman & Bernard Berkowitz |

How To Be Your Own Best Friend |

Self-Help |

| 572 |

12/6/20 |

Ludwig Bemelmans |

Madeline |

Children’s |

| 573 |

12/7/20 |

Donna Leon |

Quietly In Their Sleep |

Mystery |

| 574 |

12/7/20 |

Norman Dodge |

The Month at Goodspeed’s Book Shop September 1932, Vol. IV No. 1 |

Books |

| 575 |

12/8/20 |

Norman Dodge |

The Month at Goodspeed’s Book Shop June 1932, Vol. III No. 10 |

Books |

| 576 |

12/9/20 |

Ludwig Bemelmans |

Madeline’s Rescue |

Children’s |

| 577 |

12/10/20 |

Norman Dodge |

The Month at Goodspeed’s Book Shop October 1932, Vol. IV No. 2 |

Books |

| 578 |

12/11/20 |

Alan Burt Akers |

Secret Scorpio (Dray Prescot #15) |

SF & Fantasy |

| 579 |

12/12/20 |

Pascal Garnier |

Gallic Noir: Volume 3 [The Eskimo Solution / Low Heights / Too Close to the Edge] |

Mystery |

| 580 |

12/12/20 |

Norman Dodge |

The Month at Goodspeed’s Book Shop November 1932, Vol. IV No. 3 |

Mystery |

One of the standouts of this penultimate set of ten books is John Ashton’s History of Bread. My copy is a reprint of the book originally published well over a hundred years ago, in 1904. The book is a delightful and breezy read, if a bit Anglo-centric. And along the way the reader will learn lots of facts and lost knowledge about wheat (and its analogues), bread, and bread-making. Accompanied with contemporary illustrations. Recommended.

About the best thing I can say about Black Helicopters Over America is that I kept it, though only for the quasi-meticulous timeline of sightings during the two phases of this odd mania. The first may be related to cattle rustling in the 1970s; the second to the usual whack-a-doodles which seem everywhere nowadays. All I can say is that Jim Keith really phones it in in this little volume. It’s like he wasn’t even trying anymore. That, or he drank so much Kool-Aid that his earlier penchant for quasi-critical thinking was drowned in sugary true believer’s tomfoolery, though anyone who give credence to Alternative 3 can’t truly be said to be all that critical of a thinker.

| # |

Read |

Author |

Title |

Genre |

| 581 |

12/15/20 |

Alan Burt Akers |

Savage Scorpio (Dray Prescot #16) |

SF & Fantasy |

| 582 |

12/16/20 |

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Rupert Hughes, Samuel Hopkins Adams, Anthony Abbot, Rita Weiman, S. S. Van Dine, John Erskine, & Erle Stanley Gardner |

The President’s Mystery Plot |

Mystery |

| 583 |

12/17/20 |

Jim Keith |

Black Helicopters Over America: Strikeforce for the New World Order |

Wacko |

| 584 |

12/17/20 |

Ivan T. Sanderson |

Safari In East Africa |

Nature |

| 585 |

12/18/20 |

Roald Dahl |

George’s Marvelous Medicine |

Children’s |

| 586 |

12/19/20 |

John Ashton |

The History of Bread: From Pre-Historic to Modern Times |

History |

| 587 |

12/19/20 |

Lois Austen-Leigh |

The Incredible Crime |

Mystery |

| 588 |

12/19/20 |

Norman Dodge |

The Month at Goodspeed’s Book Shop December 1932, Vol. IV No. 4 |

Books |

| 589 |

12/20/20 |

Kenneth Bulmer / Alan Schwartz |

The Key To Irunium / The Wandering Tellurian [Ace Double H-20] |

SF & Fantasy |

| 590 |

12/20/20 |

Kehlog Albran |

The Profit |

Humor |

While I hesitate to promote yet another book in the Dray Prescot series, especially as I have already mentioned another of these already in this brief survey of my last hundred books, I have already made some mention before on these blog pages of the other best works in this last set of ten books: My Opinions: Incest and Illegitimacy and The Barbarian West. So I will say that Golden Scorpio is a worthy finale to the Vallian Cycle of the Dray Prescot books, with a swaggering set piece battle as our hero once again assumes a new mantle to raise an army to defend all that is good and true. The book is full of thrilling incident and new characters destined to play their part in the new world Dray Prescot is involved in making.

As a final note, I’ll simply say that this parody of the classic by the mystical Lebanese poet turned out to be pretty damn funny. For what is obviously a throwaway publication to lick up some of the pennies dropped by people who were tired of seeing the original on every bookshelf (it was published by Price/Stern/Sloan, which should give you that clue), The Profit turns out to have some real jokes, some real insights, and a real appreciation both of the source material and the readers of Gibran’s apparently immortal words.

| # |

Read |

Author |

Title |

Genre |

| 591 |

12/22/20 |

Alan Burt Akers |

Captive Scorpio (Dray Prescot #17) |

SF & Fantasy |

| 592 |

12/23/20 |

Alan Burt Akers |

Golden Scorpio (Dray Prescot #18) |

SF & Fantasy |

| 593 |

12/24/20 |

Rod L. Evans |

The Angels Knocking on the Tavern Door: Thirty Poems of Hafez |

Poetry |

| 594 |

12/24/20 |

David Baldacci |

Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge: The Book of Mnemonic Devices |

Reference |

| 595 |

12/24/20 |

Kenneth Robeson [Lester Dent] |

The Squeaking Goblin |

SF & Fantasy |

| 596 |

12/26/20 |

Alfred Jordan |

My Opinions: Incest and illegitimacy |

Wacko |

| 597 |

12/27/20 |

Charles Lee Magne |

The Negro and the World Crisis |

Wacko |

| 598 |

12/29/20 |

Rose Estes |

Return to Brookmere (Endless Quest book #4) |

D&D |

| 599 |

12/31/20 |

Colin Dexter |

Service Of All The Dead / The Dead Of Jericho |

Mystery |

| 600 |

1/2/21 |

J. M. Wallace-Hadrill |

The Barbarian West: The Early Middle Ages, A. D. 400-1000 |

History |

Once again, these last hundred books saw me turning most often to mysteries (approx. one quarter of the books read). A puzzlingly good one is this arch work by Peter Dickinson, The Old English Peep Show. It kept me guessing, even as I was certain I had it all figured out in my head. I’ll be back sometime this month (I hope), to give you the further statistical breakdown on all these books, now that it seems the world isn’t ending.

The lists of previously read books may be found by following the links: