“I Read It So You Don’t Have To” Department

Doomsday: The End of the World–A View Through Time by Russell Chandler is a meandering, badly held together set of essays about human ideas and experiences with the end of all things. The book is strongest when it dives into modern Christian apocalyptic thought and history. It is weakest when it surveys all aspects of End of the World ideas in the human record, which unfortunately is what this book purports to do.

Until I reached Chapter 18 I fully intended to sell, donate, or otherwise dispose of this book in an appropriate manner. It is not a “bad” book per se, just rather bland and imprecise, as might be expected from a Christian author residing in Solvang, California. There are better books about the End of the World out there, and Russell Chandler quotes and cites many of those better books in his survey course on eschatology which he titles twice as Doomsday: The End of the World–A View Through Time. The inability to choose between “doomsday” or the “end of the world” is symptomatic of this inoffensive volume collecting tertiary research gleaned from the betters mentioned just above. The author proves unable to choose between insights into modern Christian views of Judgement Day (his strong suit), or an overview of Last Days fears, thoughts, and experiences.

I pulled this book from my shelves as part of my ongoing ‘read and release’ program, wherein I am winnowing my books by reading them and then letting go of those books I do not need. Chandler’s book seemed to be just such a volume as I plodded through the early disjoint chapters through which one could easily discern the outline the author had probably typed out in WordPerfect as he sat down to wrangle his disparate material into a single book. The first two-thirds of the book reads much like most grade school book reports: topic sentence, paragraph about topic sentence, and then this happened, and then this other thing. Done. Next topic. He purports to frame his book by referencing the Roman god Janus (he is careful to mention that Janus is a “mythological” Roman god, in case you were wondering), who, Chandler says, as “the patron of beginnings and endings, is a perfect symbol for this endeavor”, i.e., his book, “a hybrid book, a combination of history and futurology.” But the book is less hybrid and more a flawed combination of mismatched parts, oil and water in the hands of the workmanlike religion editor for the Los Angeles Times.

During the current era of the “big-bangers,” the idea of cyclic cosmology has attracted some stellar proponents.

I see what you did there…

The Janus frame is used to transition from reflections on historical catastrophes and doomsayers to contemplation of modern scientific disasters and ends which may come to pass, and then is left to go hang for pretty much the rest of the book. What truly irks me about this frame is not the fact that it is a jerry-rigged bailing wire structure used to tie together his not-quite-random chapters, but that Chandler misses or is ignorant of the most salient fact about the (mythological) Roman god Janus: In ancient Rome his temple’s doors were open during wartime and closed (quite infrequently) in times of peace.* This startling ignorance is matched by his uncritical view of most of the non-Biblical, non-Christian content he reviews in his book. Along the way he seems to reveal a more mercenary vision of truth than his Christian ideals might support.

That could take nearly forever, however—about 1033 years. That’s ten billion plus another twenty-three zeros.

No. No it’s not. That’s not right. Not right at all. What if anything does that last sentence even mean?

Mr. Chandler is credulous and also easily impressed by strong book sales. For example, though he is quite strident against the inanities and the superstitious nonsense of the New Age (Chandler even wrote a book about it, which he cites in his endnotes), the author fawns almost shamelessly over one of history’s all-time great conmen (present company excluded, of course): Nostradamus. An entire chapter is devoted to — ahem — spent on the Jeanne Dixon of Catherine de Medici’s reign. After reporting the most credulous accounts from true believers and popularizers seeking to sell books, Chandler gives a fair and balanced two paragraphs to the debunker James Randi, who tore apart the perhaps purposely abstruse quatrains of Nostradamus in a 199o book. The second paragraph, however, only points out that “bookstores couldn’t keep Nostradamus books in stock; Randi’s languished on the shelves.” Chandler then quotes an apologist for the vague and confusing language of Nostradamus, who then pleads for a core of accurate predictions that “no one has been able ‘to dismiss out of hand'” — this only three paragraphs (comprising five sentences) after Randi was quoted doing just that.

In essence, scoffs Randi, just say Nostradamus—a takeoff on the line urging youth to “just say no” to drugs.

Explaining jokes is my forte, too

The book is overly cited, though one cannot accuse it of hiding behind footnotes, since it hides all the notes themselves at the end like so many other publications fearing to turn off readers with the evidence of actual research. The works cited are — for the most part — tertiary studies of the doomsday thesis, which Chandler has collated into his book in hopes of cashing in on the fin de siècle interest of the time (the book was published in 1993). Those cited works are almost always better written, though you’ll have to hunt and peck to find them, as Chandler makes up for copious endnotes by failing to provide the reader with either a bibliography or an index. The endnotes themselves show how the author skimmed his own survey sourcebooks to craft his own, for turning to the endnotes often reveals that that telling quote from original sources is merely cribbed, excuse me, “quoted in”, another’s work. Chandler even feels the need to add an endnote citation for T.S. Eliot’s classic line “not with a bang but with a whimper”, perhaps meaning that the Los Angeles Times religion editor only stumbled upon the poetry in “21. Quoted in [Daniel] Cohen, Waiting for the Apocalypse, 183.”†

I’m reporting on only a few from my Apocalypzoid File here. I’m saving my extensive—and growing—collection of personal predictions from sign-hoisting apostles of future fright for another book I want to write someday. That is, if—or as long as—their predictions are wrong.

They were, but he didn’t

On the other hand, Russell Chandler was writing before the Internet made it easy to garner information from Wikipedia and thousands of other flower-like blooms of information now readily available at our finger tips at the mere cost of incessant advertising and the loss of byte-sized nibbles from our souls. On the other other hand, as a reasonably well-read Christian writing about religion news, one assumes that Chandler would own several editions of the Bible, making it surprising that his actual Bible citations reference a slumgullion stew of different versions, including the New American Standard Bible, the Revised Standard Version, and the New English Bible — though he prefaces his work with the boilerplate assertion that, unless otherwise indicated, Bible quotes in his book are from the New International Version. (Most quotes seem to be from the King James Version, for what it’s worth.)

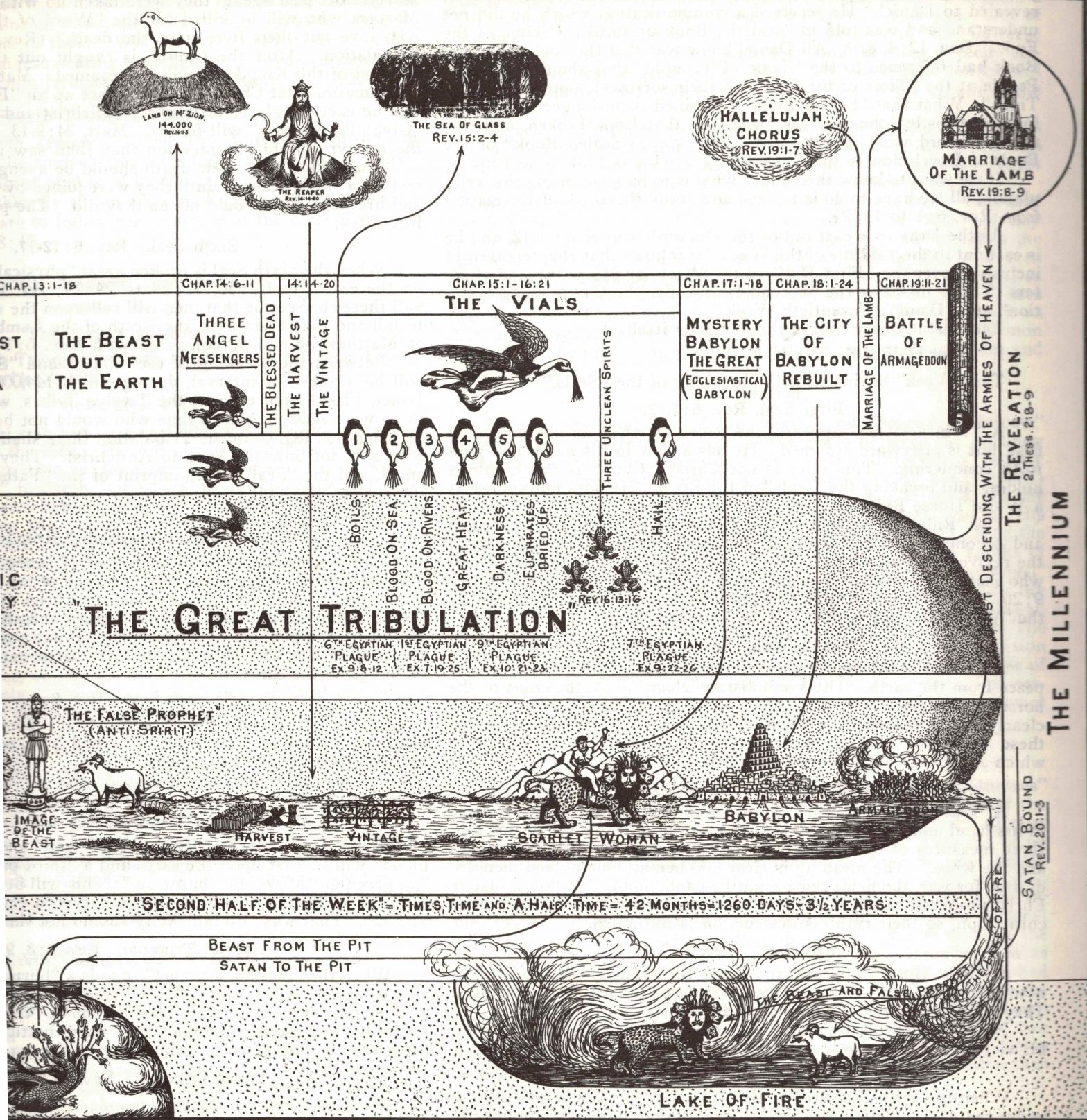

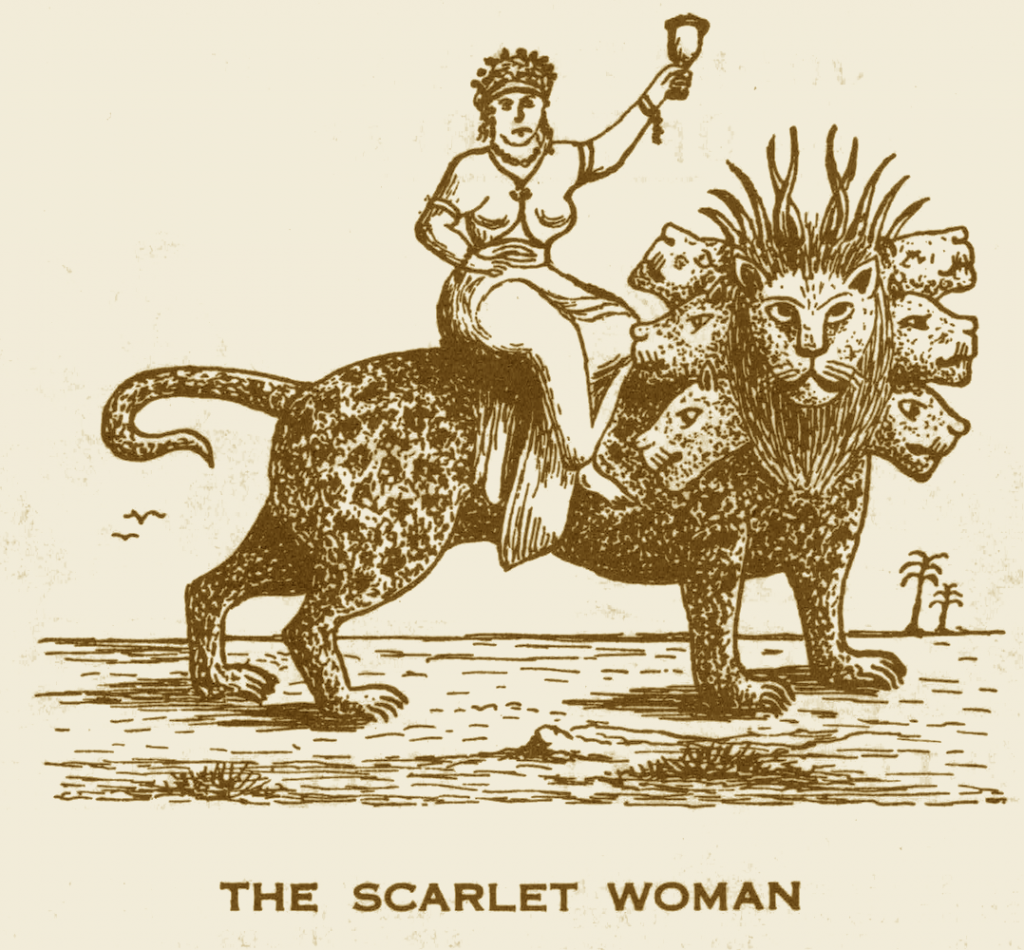

He is at his best when writing about what he knows most about,‡ the history of and bases for modern Christian apocalyptic thought. In particular, Chandler’s chapter on John Nelson Darby and his eschatological heirs is one of a few that saved this book from my donation pile; the history of Dispensationalism is fascinating to me as a son of the Bible Belt. And in eight pages in his chapter on fundamentalist End of the World views, he very clearly lays out the so-called ‘thinking’ behind talk of the Rapture and the Tribulation, as well as the differences between various millenarian Christian sects. Anyone who is curious to uncover from just where those strange prophecies of a final battle in the Middle East arose will find the explication with accompanying list of relevant Bible verses to be invaluable.

These “signs” are more “perceived” than “believed,” more empirical than prophetical. We don’t have to read them back into the words of the biblical prophets to know that ours is a different era; these times cannot be confused with prior times.

But we must not retreat into escapism. It’s irresponsible to sit back, believing that doomsday is right around the corner, so come hell and high water: Let the bad times roll. We’ll all be rescued before the End really comes.

If you are confused, check your watch … or your iPhone

I’m sure Mr. Chandler is a nice guy. He certainly comes across as one in his writing. He appeals for respect for one another amid strident calls for schism and divisiveness. His language is calm and well-mannered — or, to put it another way, bland. Thus it is a surprise when he describes the conservative preacher Tim LaHaye§ as “short of stature but long on invective”, and this reader found himself searching for the endnote that seems to accompany every other creative turn of phrase.

Year 2000 is drawing Christian mission groups like particles of steel to a megamagnet.

Like sands through the megahourglass, so are the days of our lives

Of course, we also have to remember that this book and author were a product of their times. The work is written in response to a demand caused by the (then) upcoming chronometrical rollover to 2000 A.D. It may be hard for us living on the gristle of the 21st Century to recall or realize just how much fascination still existed in human hearts for the promise and terror of the upcoming Millennium. The New Age was no longer quite new, being another one of those poorly parented children of the 70s, but was still turning its stoned attention weakly to the next bright shiny thing (something it was to continue doing after the year 2000 until the Mayan end of the world failed to materialize in 2012, instead gifting humanity with yet another mediocre John Cusack movie).

as God’s hand has gradually disappeared from the aimless handwriting of secular historians, the prophecy writers have leaped into the gap.

Most of the aimless handwriting now done on fancy word processors, natch

But Chandler’s ultimate failure is that he draws no conclusions from his material. He does conclude his book, having forgotten almost entirely his conceit about the Roman god Janus, with a personal statement of belief about the End of Days. His belief, however, like many other beliefs in our current age, seems entirely unaffected by the wide-ranging material he has just researched. He has taken a Cook’s tour of the end of time, dragging us along with him, but we end the trip with only a few snapshots and postcards, and very little learning. Look elsewhere if you wish to learn about topics such as the roots of apocalyptic thought (try Norman Cohn’s masterful Cosmos, Chaos and the World to Come or Paul D. Hanson’s The Dawn of Apocalyptic), or what happens in a social group on the day after doomsday (the classic study is When Prophecy Fails by Leon Festinger, et. al.), or just why humans seem innately drawn to predicting the future (even the old popular account Science, Prophecy and Prediction by Richard Lewinsohn is superior, which may be why Chandler cites it frequently).

Admittedly, it’s hard to discern the meaning of Bible prophecy. From the mainline and liberal perspective, that’s a built-in “given.” And that in itself may be a prime reason why eschatology receives little attention in most mainline circles.

Written when “liberal” was not a dirty word, and could be used publicly to describe (as here) Christian churches

All societies have had their seers, prophets, and prognosticators. We call ours pundits, pollsters, or economists. But to recognize this truism is to overlook the salient fact about prophecy, which is that prophecy (like apocalypse itself) is a literary construct — nothing more, nothing less. Only in literature can all the elements of prophecy be fulfilled. When a wise woman or a native shaman or a “magic black man” makes a prediction, it is only in literature that things can come to pass just as predicted. All other prediction seems to involve shoving round pegs into the square holes left by the past. If you recall that most prophecies were written after the events they predict, you will know a great secret.

The times we live in at this moment, though plagued by powerful gadflies who seek to create the Armageddon they (perhaps) fervently believe in, seem less inspired by Nebuchadnezzar’s magic four-layer statue and more by Genesis 11. Anyone who spends any amount of time reading social media or news not tailored specifically to his or her own political beliefs will recognize that our language has been confounded, and that we do not understand one another’s speech. One hopes that our Balkanization of speech will slow before it becomes entirely impossible to communicate, but only time will tell.

“now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do.

“Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.”

Genesis 11:6-7 [KJV]

(some may see the hand of Putin rather than the jealous Yahwist God)

* I know that the building in Rome is supposedly “not a temple” or “not a normal temple”. Whatever, Wikipedia.

† Even his first mention of the Daniel Cohen book is fraught with this problem, as the first citation of Waiting for the Apocalypse notes that the quote Chandler uses is “cited in” some random article from the now-defunct Omni magazine. Which is strange, as it seems clear that Chandler had the Cohen book when he was writing his own.

‡ Another insight from The Book of Duh.

§ Tim LaHaye is now best known as the co-author of the successful Left Behind series of during-the-Apocalypse Christian thrillers, featuring the action-packed adventures of the Tribulation Force. He only receives a single paragraph in Chandler’s book, as LaHaye was still a few years away from discovering his coauthor in the sprawling empire that the Left Behind series and spin-offs have become.