The first novel featuring the adventurer, importer, sometime gun-runner Paul Harris is not as cohesive, nor as finished as the only other I’ve read in the series (You Want To Die, Johnny?), but it rollicks around Malaya and Sumatra quite successfully, kicking off the long-running series with gunshots, plane wrecks, and hot boat on boat action. Author Gavin Black—pseudonym of Oswald Wynd, a Scot born in Tokyo to missionary parents—created in Paul Harris a frustrating and fascinating character, an embittered man in a loveless marriage, who fights a rear-guard war against the collapse of colonialism in the island states of southeast Asia during the height of the Cold War. Though he is seriously flawed, Paul Harris passionately believes in his adopted land, a land he has loved since fighting the Japanese in its jungles during World War II. In this initial novel of the series, either Harris or the author lacks the confidence he evinces in the later work, and the story verges into melodrama at times, particularly when Paul Harris muses about his relationships with women. Many of these thoughts verge on misogyny, yet the author will show Harris being put in his place almost every woman in the novel; Harris eats a dish of crow more than once and is forced to face his own fallacious outlook upon that and other aspects of his world—though confronting himself does not always seem to result in change, and he seems always to retain his privileged relation (at least in his own mind) with the people resident in his ‘beloved land’.

The Japs had dive-bombed this ferry once, in the dark like this, but accurately, pasting us for about an hour, while I waited in a slit trench. A lot of men had been killed. It was something to think about, the good men who had been killed, while you went on for years, and blundered.

Paul Harris contemplates surviving only to err

The action starts in Kuala Lumpur, where Paul Harris is spending some time with his not-actually mistress Kate being Platonic and close and friendly and all. Kate is a reporter, a woman reporter, as she points out, who is writing a story about Paul and his brother Jeff, who are involved in some ill-defined under-the-table business which involves—at the very least—smuggling guns for rebel forces operating in Sumatra against the communists of Indonesia. Kate moans that a woman reporter “can’t ever be really good. Not tops. We’re not ruthless enough.” Meaning that she can’t both be Paul’s lover (in the strange Platonic sense the novel wants us to believe) and at the same time drop a dime on him to publish her bombshell story about his gun-running and what-all with his brother. They talk about how to deal with Paul’s wife, and are just heading off for drinks at the hotel (they have separate rooms, btw) when—Wham! Paul gets a call: his brother is dead, murdered in Singapore.

When I came out it was with my world broken around me, blown up, shattered. I felt sick and old.

Paul learns of his brother’s death

Paul rushes pell-mell back to Singapore, Kate in tow, to find the varmint that killed his brother. He goes to the scene of the crime, then home to his whining wife Ruth, where he meets Inspector Kang of the Singapore Police, who will dog his steps for the rest of the novel (and who will reappear in the series to come, as well). The Chinese-born Kang is scrupulously polite, though Harris is not fooled for an instant. Paul must keep quiet about most of the clandestine activities he and his brother were involved in to avoid legal entanglements from the police, and resolves to keep Kang at arm’s length.

Inspector Kang’s eyes were very cold. I think mine were, too, they were meant to be. It wasn’t just that latent hostility between a policeman and the ordinary citizen, but something that went much deeper at once, that moved into zones of feeling which knocked out reason in both of us. I didn’t like the world into which Kang was fitting so nicely thank you. And he thought my world should be liquidated, that it was only a matter of time until it was.

Paul Harris meets his bête noire, Inspector Kang

From here on out we have action, action, action, until the usual third act rest and recuperation, then more action, surprise twists, and a resolution that was strangely satisfying to me. In the meantime, there are betrayals and disappointments, both suffered and inflicted by Paul Harris himself. He proves himself a poor judge of female character, at minimum, and is upbraided with honest and reasonable heat by those he thinks himself more civilized than, the very people he would either help in his paternalistic fashion or whom he would exile entirely from the political process due to their inaptness for rule. Along the way Gavin Black paints us a portrait of a world few Westerners know well, a world which the author obviously lived in and loved. (One can be fooled however, as Wynd returned to his native Scotland immediately after the war, never to return to southeast Asia.) The Malaya that Mr. Black evinces is a hodgepodge of many and varied influences and cultures, all vying for supremacy even as another syncretic culture is being created out of the mix.

Mrs Flores opened a shutter and there was more light to see a room crowded with trophies of disordered living, each piece like a little symbol of an eccentric ambition which had petered out. There was a Victorian rocker, a contemporary sofa, a dead gramophone and a mahogany piano. There were Chinese jars with wilted feather plants in them, and across one corner a cocktail cabinet which was open to show the glasses and the mirrored surfaces.

Paul Harris visits the cheaper district of Singapore

Like many noir heroes, Paul Harris takes it on the chin, though the enemies he claims to be fighting, the warlords and communists, inflict no damage as severe as that given him by many of the women in his life. From the women, he gets it in the gut with both barrels. It is startling to have such a strong and assertive character receive his comeuppance not once but multiple times in a single book, each time suffering attacks on the very foundation stones upon which his character rests, yet each time reasserting himself and groping about until he comes to the conclusion (mostly) that he was right all along. What’s not clear to me is whether the author meant to show a man who cannot be swayed from his patronizing, colonializing ways by mere evidence of his wrong-headedness, or whether the decades since this book was written in 1961 have so changed the zeitgeist that I have become incapable of picking up the cues and clues that would demonstrate how Paul Harris’s paternalistic anti-communism is always going to be the right choice, even in the face of strong attacks against his down-putting ways.

‘We are not to be relied on, Mr Harris. How sensible not to trust me with your secrets. We are too emotional, I think. Perhaps we imagine wrongs that are not being done to us. Maybe we should accept politeness at face value. Your instinct was surely most sound. Such a fool, knowing too much, could be most dangerous. Now will you go? Will you go to hell?’

It’s not me … it’s you, as Paul Harris learns … maybe

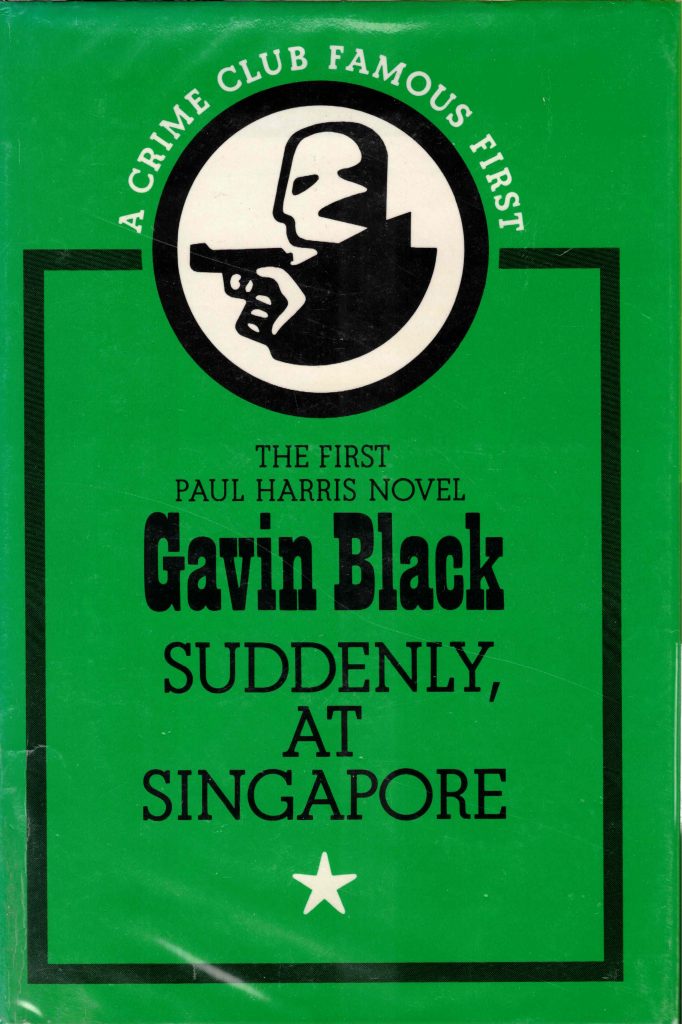

Even though this book is not as cogent and complete as the other one in the series that I have read, it is easy to see why Joan Kahn chose Gavin Black to be one of the authors to whom she gave her imprimatur while helming the Harper Novels of Suspense. (She also championed at least one book published under the author’s own name, Oswald Wynd’s The Blazing Air.) Whatever flaws this first in the Paul Harris may have, Suddenly, At Singapore packs plenty of action into a complicated yet reasonable plot with an unusual and vibrant locale. Though we may doubt the protagonist’s views of the world he lives in, we are convinced that he certainly believes in them, and thus he allows us a glimpse of a decaying world now forever lost.

It is always safe to lead the French to the Chinese, the only other people in the world they will allow any claim to be civilisé.

Paul Harris indulges in social niceties or racism, take your pick

And this ‘otherness’, this revelation of a time forgot, the hopelessly sincere passion manqué of a Cold War Asia rotting in the fetid heat beneath a rising communist sun, speaks across the half-century which has come and gone in a flurry of sound and fury, and seems more foreign to my ear than the latest K-Pop sensation. If I were to read a Soviet-era rendition of a communist 007, fighting the good fight against the imperialist West while using his plentiful sex appeal along with his rock-hard socialist principles, it would seem no more cognitively dissonant than Paul Harris does as an action hero in the formerly British Malaya. Yet both of these, the fictitious Soviet spy and the fictive hero created by Gavin Black, both thrill me where most current suspense protagonists only cloy. Thus Paul Harris enlivens tropes that have become stale, while he startles with sincere convictions no longer fashionable, nor perhaps even extant. From the sultry humid jungles of his beloved island, he brings a refreshing take on the action novel, while enduring painful lessons about the limits of his own worldview and world—lessons he does not always seem to learn.