Roald Dahl’s classic work of children’s fiction, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, is neither very good nor very bad, unlike the ridiculous stereotypes of children presented to us by the author. The book is ‘classic’ in the both senses: old and made into a movie. (Two, actually, but the second does not improve the Gene Wilder version, whereas Gene Wilder’s movie greatly improves the book.) The book is at times ludicrous, starkly depressing, boring, implausible or unbelievable (à votre goût), funny, heavy-handed, sardonic, and sweet. Unfortunately, it very rarely manages to be more that one of those things at a time, a failing which surprised me given the hype this book has received from friend and foe alike.

To speak of the friends and foes first, you can pick up a first edition of the book, just 55 years old now, for $6,500. Many people have loved the novel, including Tim Burton, who ruined the perfectly good movie already at hand. Several lists (if you’re into that sort of thing) have included Charlie et. al. in their ‘best children’s books’ assemblages, such as the Grolier 100, or Time magazine’s 100 Best Young-Adult Books. I suspect it made the lists because people think children are stupid. Its foes include those who object to the colonializing ideas behind the Oompa Loompas—who were African pygmies in the first published versions—though to this reader the minuscule people seem to be just another half-baked idea poorly executed in this hodgepodge of a book.

The main problem with Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is lack of focus and voice. I first thought that Roald Dahl simply could not write for children, just as Margaret Atwood proved disastrous when she attempted to preach to kids in her trainwreck of an illustrated children’s book, Princess Prunella and the Purple Peanut. However, I have come to believe that the problem with Dahl’s book is that he had too many ideas, and tried to shoehorn them into a book for kids whether the idea belonged there or not. The focus upon sweets and chocolate as a glorious thing is perfect for youngsters who have not yet experienced the excitement of pubertal acne, and works (mostly) as a tentpole around which to revolve this novelette. But mixing in direst poverty, tut-tutting criticism of modern parenting, and industrial espionage just makes for a mess, and the potentially sweet core becomes instead just a soggy lump.

“Did you know that he’s invented a way of making chocolate ice cream so that it stays cold for hours and hours without being in the icebox? You can even leave it lying in the sun all morning on a hot day and it won’t go runny!”

“But that’s impossible!” said little Charlie, staring at his grandfather.

“Of course it’s impossible!” cried Grandpa Joe. “It’s completely absurd! But Mr. Willy Wonka has done it!”

Roald Dahl at his best, proving Aristotle’s maxim that a plausible impossibility is preferable in poetics to an implausible possibility

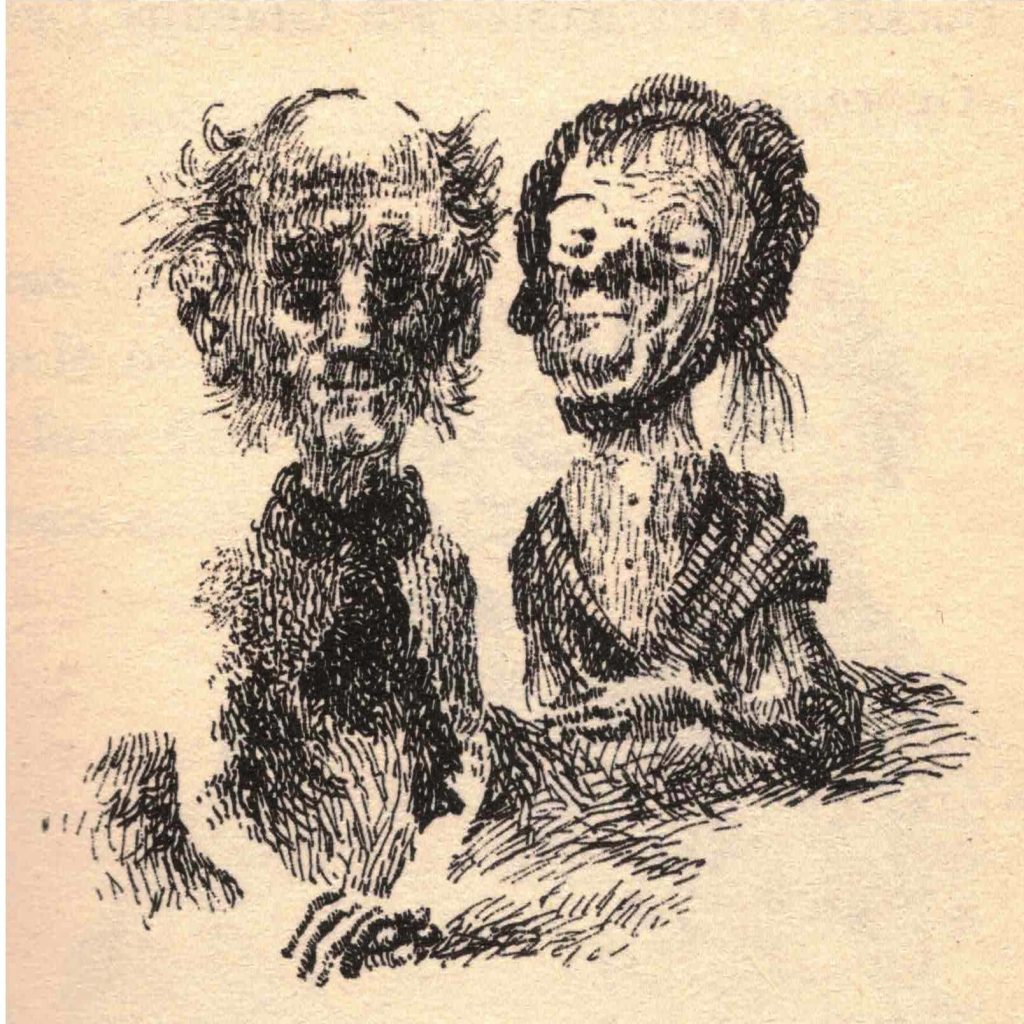

The problems start on the very first page, when we are introduced to Grandpa Joe and Grandma Josephine. Here is what they look like:

(Note: though the cover shown above is from a later edition (and is pretty pedestrian art), this and all other illustrations are reprinted from the first publication, the work of Joseph Schindelman. So this is what the author expected his creatures to look like.) The original cover had Charlie’s face, emaciated with haunted eyes, conveying his extreme poverty and eternal hunger. From what the book tells us, Charlie and his family are the only hungry people in all the world; all others we meet are chubby candy store owners, fat rich kids and parents, self-absorbed rich kids and parents, etc., etc.

So right away the lines are drawn pretty clearly (except for the somewhat impressionistic cross-hatching illustrations) between the hungry extended Bucket family and the sated yet consuming rest of the world. Only the mysterious Willy Wonka stands apart from this lopsided dynamic, while five-sevenths of the poor class (i.e., Charlie’s family) stay home in their ramshackle house all day, waiting for Charlie to return home from school and Mr. Bucket to return home from his job. His job at the toothpaste factory. Screwing on the tops of toothpaste tubes. He will later lose his job because the factory shut down, which is surprising given the fact that the entire community must be suffering from serious tooth decay given everyone’s predilection for candy and chocolate.

In the evenings, after he had finished his supper of watery cabbage soup, Charlie always went into the room of his four grandparents to listen to their stories, and then afterwards to say good night.

Every one of these old people was over ninety. They were as shriveled as prunes, and as bony as skeletons, and throughout the day, until Charlie made his appearance, they lay huddled in their one bed, two at either end, with nightcaps on to keep their heads warm, dozing the time away with nothing to do.

Roald Dahl came close to writing Soylent Green nine years too early

Since Charlie walks past Wonka’s chocolate factory every day to-ing and fro-ing from school (which is mentioned only as another place for Charlie to starve), he is tortured by the delicious smells emerging from behind the great walls around the plant, and listens avidly to his Grandpa Joe’s tales of the amazing Willy Wonka. Once a year, Charlie gets a candy bar for his birthday (the smallest bar, natch), and then nibbles slowly at it to drag out its consumption a full month. Then in the book—blah, blah, blah—the golden tickets, the media goes wild, the bad kids get them, and Charlie doesn’t have a chance. But it’s his birthday, and … he doesn’t have a chance.

“You never know, darling,” said Grandma Georgina. “It’s your birthday next week. You have as much chance as anybody else.”

“I’m afraid that simply isn’t true,” said Grandpa George. “The kids who can afford to find the Golden Tickets are the ones who can afford to buy candy bars every day. Our Charlie gets only one a year. There isn’t a hope.”

Comforting words from Grandma Georgina, followed by a reality chaser

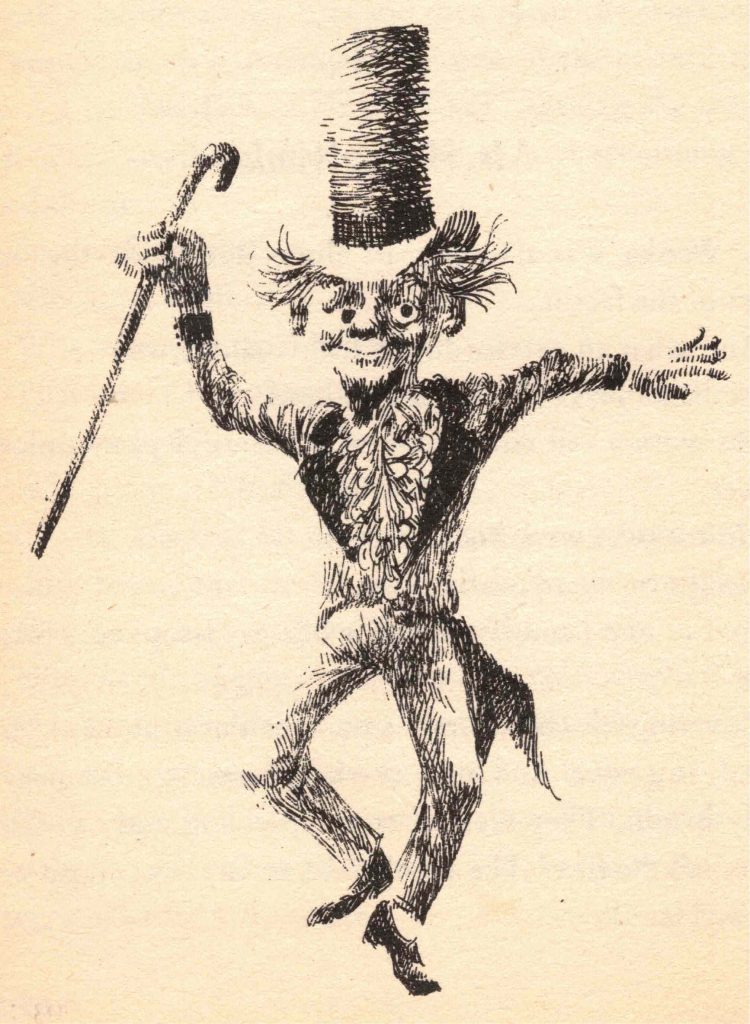

Of course, you know the story, or think you do. I know I did, or thought I did. Or … wait a sec, now I’m confused. Anyway, everything plays out just as you expect and know, and so Charlie gets the last ticket—on the very last day!—and he and Grandpa Joe go off to meet the strange and incredible Willy Wonka.

Most everything you saw happen in the movies happens here: chocolate rivers, gobstoppers and gum, squirrels and nuts, magical TV cameras for chocolate, and so forth, with the end result that only Charlie is left to receive the bestest prize of all: ownership of Willy Wonka’s factory! Yippee.

Okay. Can we stop for a second and talk about how stupid Mr. Wonka’s plan is? Put five tickets randomly into the millions (well, at least tens of thousands) of candies sold by this huge enterprise, the finders of which visit the factory, and whomsoever can manage not to glutton or stupid their way out of the tour group becomes the new owner of the plant? Why not just adopt a stray puppy and make it CEO? The idea is as ludicrous as asking the Internet what to name a boat, or what flag a country should have, or who should be president. In the real world the tickets would have been found by agents of Slugworth and Fickelgruber and Prodnose, Wonka’s rivals and the raisons d’être for closing his factory gates to the world.

Which is another point. The plant could provide needed jobs for at least Charlie’s father, but industrial spies have made it more practical for Wonka to import foreign labor on H1-B visas than to hire domestic workers. ‘Tis a very strange world that Dahl creates.

“Mind you, there are thousands of clever men who would give anything for the chance to come in and take over from me, but I don’t want that sort of person. I don’t want a grown-up person at all. A grownup won’t listen to me; he won’t learn. He will try to do things his own way and not mine. So I have to have a child.”

Makes sense when Mr. Wonka explains it

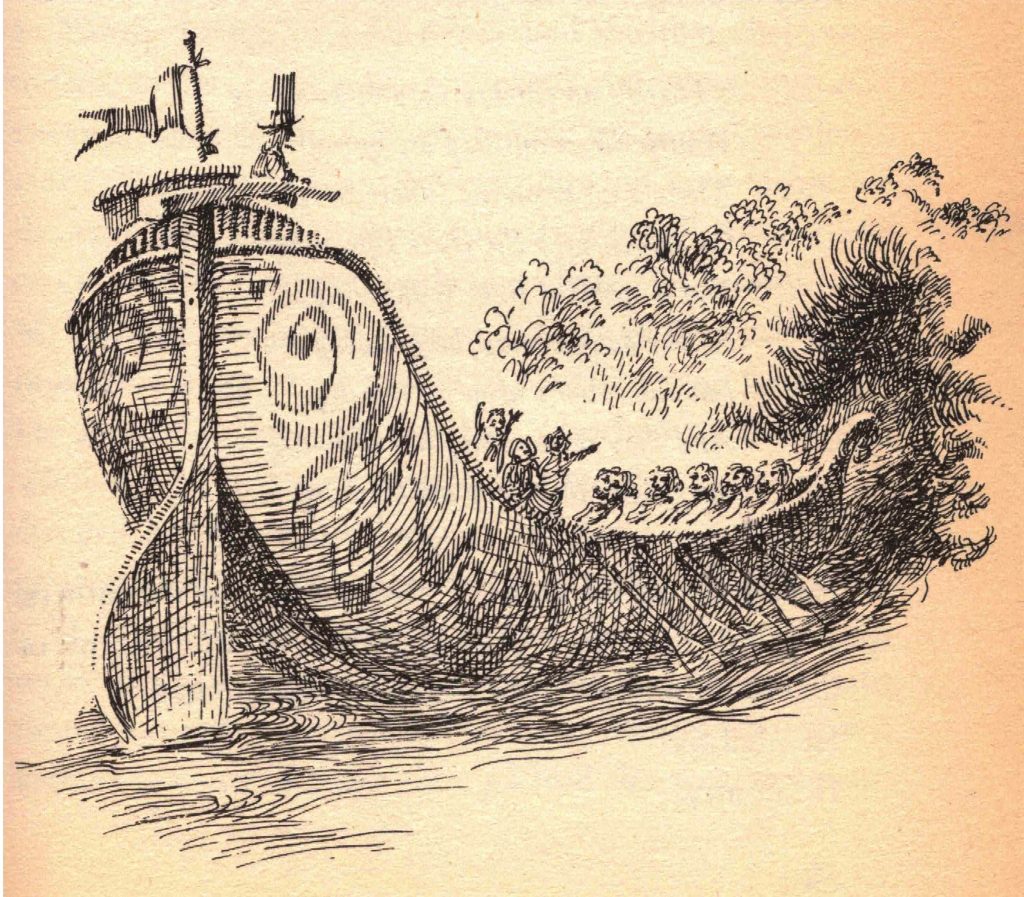

Now the movie and the book are really very similar, in that all the good parts of Roald Dahl’s book are in Gene Wilder’s movie. And the parts that are different in the movie make the story better—more cohesive, less depressing, more fun. For instance, there’s no Slugworth-wants-you-to-steal-a-gobstopper plot point in the book; its inclusion in the movie tightens up the story immensely. Ditto for the fizzy lifting drink, which is just one of the rooms passed in the crazy boat ride in the book. Speaking of crazy boat rides, that’s totally in the printed story, and is just as crazy, with almost the same mad poetry from Willy Wonka. (Though the boat itself is an enormous Viking ship with a hundred Oompa Loompas manning the oars.)

But in the book many of these episodes are only half-drawn and lie flat on the page. Whereas Wilder’s Wonka has a rakish and dangerous charm, Dahl’s version is clever but boring, like a spinster aunt trying to entertain children by touting the ‘scrumptious’ candy she has brought. Also the starvation. Oh, did I not mention that?

There is an entire chapter of the book delightfully titled “The Family Begins to Starve”. At that point in the story, Charlie has managed to acquire two (2!) Wonka candy bars, spending money the family could have spent on cabbage, and finding—of course—no Golden Ticket within. Now the father has lost his job, and the thin, watery cabbage stew becomes thinner and more water, less cabbage, and the entire family begins to face the very real—and realistically depicted—threat of starvation. The grandparents try to give Charlie some of their food, but the noble idiot refuses it, even though he is now the only one leaving home on a regular basis, as his dad has only occasional work shoveling snow. The dire and potentially fatal consequences of hunger are limned by Roald Dahl with too much veracity for a children’s book, and I found myself wondering just what I was supposed to be reading. It really is one of the saddest passages I’ve read in a kids’ book without the death of a pet.

And every day, Charlie Bucket grew thinner and thinner. His face became frighteningly white and pinched. The skin was drawn so tightly over the cheeks that you could see the shapes of the bones underneath. It seemed doubtful whether he could go on much longer like this without becoming dangerously ill.

And now, very calmly, with that curious wisdom that seems to come so often to small children in times of hardship, he began to make little changes here and there in some of the things that he did, so as to save his strength. In the mornings, he left the house ten minutes earlier so that he could walk slowly to school, without ever having to run. He sat quietly in the classroom during recess, resting himself, while the others rushed outdoors and threw snowballs and wrestled in the snow. Everything he did now, he did slowly and carefully, to prevent exhaustion.

Charlie resolves to starve quietly rather than noisily demand help from the people all around him with full bellies

Not to worry. All this pathos and bathos will be quite forgotten by the time Charlie is adopted by Mr. Wonka and goes to live in Neverland—er, I mean the factory. And the fact that Charlie spends found money on candy for himself rather than nutritious food for his entire family is forgiven, as the book teaches us that it is best to trust to ridiculous amounts of luck rather than to ask for help in times of need.

And so I won’t ever read this book again, though I’m likely to watch Gene Wilder every chance I get. I’m also a little chary of Roald Dahl’s other books, but only time will tell about those stories.

Until next time…