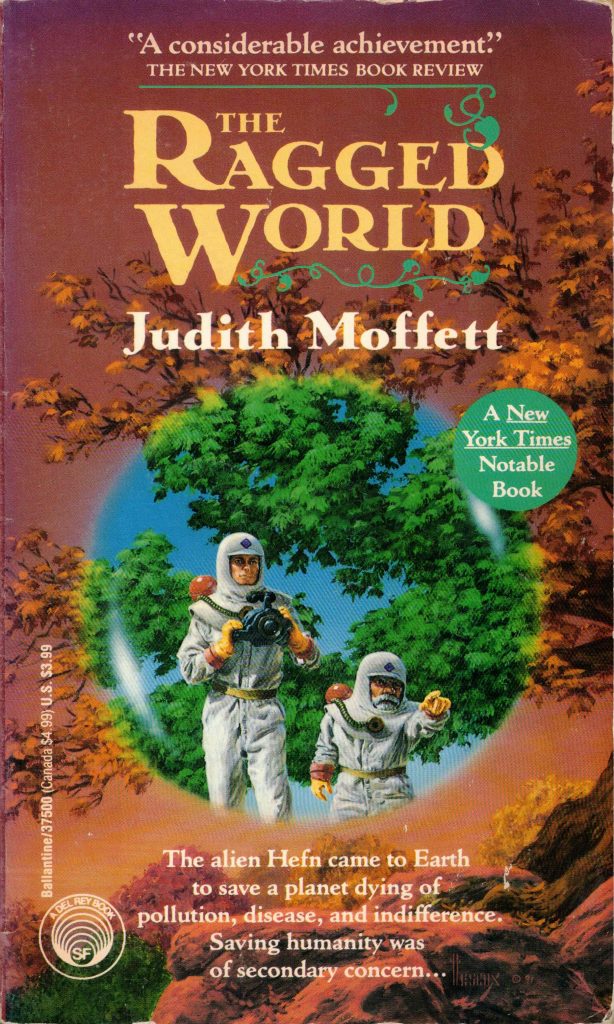

The Ragged World: A Novel of the Hefn on Earth, by Judith Moffett

This ‘fix-up’ novel* about the interactions between Earth people and ecological aliens was so ponderous and so swathed in psychobabbulous platitudes that I almost began to sympathize with the Sad Puppies.† Almost. Even this pointless set of interminable tales of deus ex machina as self-help anodyne could not make me support the Puppies’ program of destructive and jealous thuggery against Science Fiction, a genre which I do love. Either play the game or don’t, people; if you really hate the game you shouldn’t try to throw the board to the ground and then set it afire, just walk away. Sorry, where was I?

Oh, yes. As I was saying, The Ragged World is a heavy-handed, boring set of seemingly endless stories about uninteresting people leading fruitless lives in the midst of an alien invasion. The science fiction elements are poor, and barely extant. I came nigh to placing this book report into the “I Read It So You Don’t Have To Department” until I discovered that this book and these stories were recipients of fulsome praise, and I wondered why. To my mind they are neither engaging, nor good science fiction. (They aren’t bad SF, either; the science is plausible and well-researched and all.) Perhaps the quarter-century which has passed since this novel appeared in 1991 (or the thirty years long gone since the original short stories were published) has so changed the mores and foci of our world that these overly earnest tales of ecological disaster and the heartbreak of HIV-AIDS seem only quaint as we watch the Endarkening of the Western World. Perhaps I am merely a reactionary reader rejecting a new voice. In any event, I cannot understand the buzz for this book, so (obviously) YMMV.

The novel itself is composed of eight short stories, five of which had been previously published separately. An introduction and an appended chronology are added to round out the book. The introduction relates almost all of the science fiction in the book (save for a few references to AIDS vaccines and some efforts at Mendelian melon growing): Aliens arrive on Earth, looking for left-behind comrades marooned here 400 years ago. Aliens leave. They come back four years later after a nuclear meltdown, and impose diktat on the planet to ‘go green’ or else. (Two pages of the seven-page introduction consists of the details of these ecological Alien Orders.) A couple of years later the Aliens rescind the ‘or else’ part of their diktat, and instead stop human reproduction indefinitely. And … that’s it. That’s the science fiction part of our story. The rest of the novel consists of the stories of ‘ordinary humans’ going about their ‘ordinary lives’ and intersecting the Aliens in ‘surprising ways’.

All right, yes, you’re right; those last air quotes are overly sarcastic, and there’s nothing surprising about the human-Alien interaction. In fact, the Aliens (Ms. Moffett names them the Hefn) function primarily as a folkloric or prophetic plot device to attempt moving the shapeless masses of the author’s stories, and as a deus ex machina to solve intractable problems she writes herself into. As an example of folklore, two stories—“Ti Whinny Moor Too Cums at Last” (originally more euphoniously called “The Hob”) and “Final Tomte”—pivot on the idea of old creatures of local mythology being the abandoned Aliens left behind in Yorkshire and Sweden, the hobs and tomtar of the chapter/story titles. (We’ll ignore the fact that the Scandinavian nisse (= tomte) existed long before Christianity in that region, and thus long before the 17th-Century visit of the Aliens to Earth.) The first of these more folklore-focused tales starts promisingly as a retelling of “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs”, as a lone American traveller on the moors discovers one of the abandoned Aliens and is forcibly taken back to his hidey-hole where he lives with six other gnomish creatures (another having just died in hibernation). But this story, like all the stories in this book, devolves into a desultory tale of futile waiting and meandering first-person pondering, brought to nought by a good old Alien memory wipe. Though the American finally remembers these events upon the Aliens’ return, the focus of the story is upon the beauty of the North Yorkshire moors and the thoughtful planning of the hiking American tourist.

She shrugged off her backpack, leaned it upright against the bridge, and pulled out one insulating pad of blue foam to sit on and another to use as a backrest, a thermos, a small packet of trail gorp, half a sandwich in a Baggie, a space blanket, and a voluminous green nylon poncho. She was dressed already in coated nylon rain pants over pile pants over soft woolen long johns, plus several thick sweaters and a parka, but the poncho would help keep out the wet and wind and add a layer of insulation.

Jenny shook out the space blanket and wrapped herself up in it, shiny side inward. Then she sat, awkward in so much bulkiness, and adjusted the foam rectangles behind and beneath her until they felt right. The thermos was still half full of tea; she unscrewed the lid and drank from it directly, replacing the lid after each swig to keep the cold out. There were ham and cheese in the sandwich and unsalted peanuts, raisins, and chunks of plain chocolate in the gorp.

Swathed in her space blanket, propped against the stone buttress of the bridge, Jenny munched and guzzled, one glove off and one glove on, in a glow of the well-being that ensue upon vigorous exercise in the cold, pleasurable fatigue, solitude, simple creature comforts, and the smug relish of being on top of a situation that would be too tough for plenty of other people (her own younger self, for one).

One of Ms. Moffett’s characters enjoys a sandwich and tea, with a side of gorp and smug relish

The Alien as prophecy weaves through the tale of another set of the novel’s protagonists, Carrie and Terry, respectively a professor of English and one of her students, whose aimless relationship begins with Terry’s bizarre response to a poetry midterm, told in the story “Remembrance of Things Future”. Worried that his strange rant may signal a psychotic break, Carrie is even more upset when Terry shows up at her home and professes no memory of the strange apocalyptic answer he wrote on the midterm. The prof tries to stir his memory by taking him to the last place he could remember, a local park, and hilarity ensues. No, just kidding, the story just keeps bumbling along until we learn that Terry, too, has had an Alien mind-wipe, that he’d seen a time portal with a human and an Alien peering through from a radioactive future, and that this future Odd Couple were trying to make a video of two deer having sex for a relative of the human. The futurnauts missed the date, however, and film only a buck bounding along and making scratches on trees, and then they see Terry and have to erase his memory, after cleverly telling him a whole lot of plot points they’re about to erase forever. Of course, it’s not forever; he remembers everything for his English professor a few days later, and the details he remembers make up crucial plot points for several of the interconnected stories threaded through the book. Terry himself goes on to become a politician just so that he can have a response plan in place for the nuclear disaster which he knows is coming from what he sees through the time portal. (And can we just pause a moment to note how poor the Aliens are at this whole memory-wiping thing? They are able to plant a post-hypnotic suggestion which makes the entire human race incapable of reproduction, but each attempt to wipe the memories of one of our main characters results in the block being lifted—once after many years and only after the Aliens return, but for Terry only a few days later because the intended victim was left in some sort of fugue state whilst taking a written exam.) This strange sequence is the lynchpin of the entire ‘novel’, and we should not forget that it centers upon the use of time-travel technology (well, time-travel-viewing technology) to make a video of two rutting deer.

But before either of us could reply, the crashing in the dead leaves began, the doe—foreordained, remembered—came hurtling up the slope toward the rocky outcrops at a dead gallop, an indistinct dun-colored shape in the dusk, hotly pursued by the second, larger, nobler shape which overtook, licked and nuzzled and finally lunged above her directly beneath the great boulder where we crouched, knocking her forward onto her knees with the force of the single thrust delivered so explosively that his hind feet left the ground—and off, down and away so swiftly we had scarcely moved or breathed till there were no deer anywhere on the twilit slope below.

So now I’ve spoiled the story for any reader who is unaware of how prophecy works in stories

Also, this might be poetry, but I’m not sure if deer porn is a basis for SF (on the other hand, see the note about Chuck Tingle below)

The other main narrative thread, a novella called “Tiny Tango” (which took 5th place in the polling for the Best Novella Hugo Award in 1990‡, back when those meant something), disquisits upon the plodding story of a woman infected with HIV more than a dozen years before the AIDS Riots of 1998-99 (one of the two science fiction elements that is not Alien-as-folklore/deus ex machina). Sandy, as we’ll call her (though Nancy is her name), changes her career path from hard-hitting research to becoming a minor biology professor at a minor college upon learning her dire news, concentrating on living a healthy, stress-free life in order to stave off the ravages of her incurable condition. She ends up living a long (everything in this book is long, lengthy, prolonged, endless, and interminable) life—if you can call it living—devoted to mediocre research in pursuit of tenure, eating healthy organic food, meditation, and attendance at her weekly HIV-AIDS support group. Her fellow sufferers and she all have to clandestinely fight their disease, as Americans are attacking any carriers they can find, forcing registration and, as mentioned, eventually rioting against those carrying the virus. Years pass. Sandy begins crossbreeding melons and performing strange solo perversions in men’s bathrooms. A vaccine is discovered (no help for those already infected), allowing a slightly less covert lifestyle for Sandy and her fellows. The Aliens arrive, don’t cure AIDS, and then leave. Then the nuke plant melts down, mere miles from Sandy’s house … and Sandy’s not there, she’s visiting her ill mother. The Aliens return, more stuff happens, and the Aliens finally interact with the biologist (who has developed full-blown AIDS by now), putting her into a deep-freeze while waiting for a cure. (Sandy is also the putative narrator of the novel’s introduction that outlines the entirety of the Alien interaction with the planet.)

I get it, to a very mild extent. To investigate the inner life of an AIDS sufferer in 1987 (when this was written, published in 1989) in the context of science fiction is of some interest, at least. I don’t find the story or the narrator very interesting, however. Perhaps, as I posited earlier, this is because of the anachronistic knowledge I have of the events since this time. Perhaps, as I believe, it is because this tale and the entire novel are banal and self-absorbed, focused on an inner life which is dispassionate and boring.

for such a long time I was myself so thoroughly alienated from the human race, the human viewpoint—that for so many years the life I had to lead was other than, and less than, a truly human life. For a person with my background, adopting the Hefn point of view is actually easier in some ways than identifying with the general human point of view.

Sandy’s introduction underscores the novel’s primary flaw, while eliding over the fact that we never actually learn the Hefn point of view (save that we cannot comprehend it)

That’s enough synopsis. There’s another primary character, Liam, the best friend of Terry’s son, who fulfills the prophecy of the failed deer porn time-travel expedition, but here is the terrible secret at the heart of this book: every character is the same. Though the plaudits for this novel praise the “convincing emotional lives of her characters” (Kirkus Reviews), this ’emotional life’ is merely a surface-level stream of consciousness musing upon whatever topic the character happens to be brooding over at the moment. This subject for overthinking might be the best way to pack for a day hike, how to create a virus-resistant cultivar, how to hide a fugitive relative from the authorities, or teen suicide, but the interior voice never varies, never exhibits dynamic changes in tone or emphasis. It is the voice of someone who lives in their head, avoiding contact with other humans, understanding social interaction by reading books and magazines from the self-help section of the bookstore. (Don’t forget, this was written in the 20th Century, when things like bookstores and magazines existed.) The interesting and idiosyncratic aspects of the novel are mere peculiarities of the author, not of the story.

Watching the way he held the doughnut, I thought—not for the first time—that I had never seen a hand more beautifully attached to a wrist in my life.

Fair enough…

Don’t get me wrong. Human stories with just a touch of Science Fiction are entirely okay; just look at much of Philip K. Dick’s oeuvre. But the SF needs to be central to the story—not just a deus ex machina. And, more importantly, the human element of the story must be present for such a tale to work. These tales, instead, seem to exhibit a fundamental misunderstanding of human nature—or at least they exhibit an ignorance of humanity beyond academics and allied intellectuals. The salient characteristic of each of Moffett’s characters is his or her loneness; not loneliness, but a preternatural focus on himself or herself with little if any regard for other people. As the New York Times Book Review puts it, everyone in this book “is a stubbornly self-possessed individual”. I have spent time at dining tables with such all-too-self-aware types; I really don’t relish spending an entire novel with them.

The cardinal sin of Science Fiction, of all genre fiction, is to be boring. And this book is boring. Boring and long. Very long. Details are piled upon detail; the pay-per-word rate must have been quite high in the 1980s at Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine. The author seems to be of the “Tell, Don’t Show” school of writing. She has a fascination for minutiae, and skips lightly over anything that might smack of real dialogue among more than two people. (Her description of a small dinner party at which “Carrie entertained them all with a sample of wacky mistakes that had turned up on student papers over the years” made me cringe.) But the worst part of the book is just how minor it all is, how little ‘there’ there is in the novel. Nothing in this novel comments upon the workaday lives lived by actual farmers, laborers, et. al., nor even less how those lives would be affected by the earthshaking arrival of the Aliens. The idea of someone blessed with a vision of the future for which they must strive to be ready (this is Terry’s story) is much better handled by John Irving in A Prayer For Owen Meany. The unknowable reality of aliens and alien planets has been underscored many times in much better novels, for example, in Lem’s Solaris. In A Ragged World, staggering events and aliens from beyond the stars leave people meandering through life … just as they were doing before the staggering events and the aliens. Mysterious aliens cross the galaxy to paralyze the Earth, and by the way they enoble the spirit of a dozen white academic types. Ooookay, then.

Look. Stories of therapy, of self-help, of recovery, all that ilk, though each story may be powerful to the person living it, and meaningful to those seeking the help offered, almost none of these stories make good fiction. Sitting through Andy Garcia’s turn as the spouse of an alcoholic in When A Man Loves A Woman is somehow painful and numbing at the same time. A movie like Ordinary People is almost as painful to live through as the reality might be, and is made more painful by its glib psychotherapeutic miracle. In A Ragged World, the Aliens provide the glibness but no catharsis, giving miraculous answers to human problems of loneliness and loss, problems to which miracles can never be the answer. (To be fair, most of the time the Aliens disdain to give anything to humans; the novel is about the exceptions.) In this book, psychotherapy, meditation, healthy lifestyle choices, and godless spirituality are front and center, and—much like a plethora of dramas in the first half of the 20th Century extolling the wonders of psychoanalysis—none of that makes for good fiction. You can write a novel about eating right and exercising daily and a balanced routine of yoga and meditation and such; you cannot make such a novel worth reading, just as a novel about going to church every week won’t hold the reader’s attention unless you throw in a little Peyton Place.

So I end up in just the same place I started, just as this book does. I still do not understand what people see in this work. Likely I am a prejudiced, non-woke, reactionary, patriarchal, inflexible bigot and asshat. That might be it. How would I know? Maybe I was just distracted by the off-putting sexual imagery of the novel: the deer porn, twelve-year-olds, and cross-country cross-dressing bathroom penis peeking. I am easily offended, no doubt. But at the end of the day, and at the end of the novel (which was a much longer time coming), I was bored and unimpressed. Takes one to know one, I suppose.

* Apparently that’s what the kids today are calling a novel made up of short stories grafted together to form a single work, sometimes with newly created introductory or interstitial material to make the thing cohere.

† The ‘Sad Puppies’, along with the more extreme splinter ‘Rabid Puppies’, were a reactionary group devoted to gaming the nomination process for the Hugo Awards, which had been one of the preeminent awards in Science Fiction before the advent of these trolls and self-dealers. Both groups sought to dominate the Hugo nominations with their own slate of authors, reacting to what they saw as too much focus upon women and persons of coloring the Science Fiction field. They had some success in gaming the system, in that their candidates swept the nominations in several categories for the 2015 Hugo Awards; those categories, however, were given ‘No Award’ in the final vote tally, as the majority of Hugo voters rejected the Sad Puppies’ slates. The group’s efforts—or rather the efforts of the Rabid Puppies—did give rise to the wild success (as such things are measured in the thimbleful-of-attention metrics of social media) of Chuck Tingle, whom I do not recommend you look up if you are both a) unaware of who he is, and b) easily offended (say, by the idea of dinosaur porn, or gay porn, or both).

‡ I am surprised to learn that I’ve recently read the winner of that year’s Hugo for Best Novella, “The Moutains of Mourning”, which was included in Lois McMaster Bujold’s own ‘fix-up’ novel, Borders Of Infinity, which was Book #376 in my books read database. It was pretty good, I thought, likely the best story in the patched together collection.