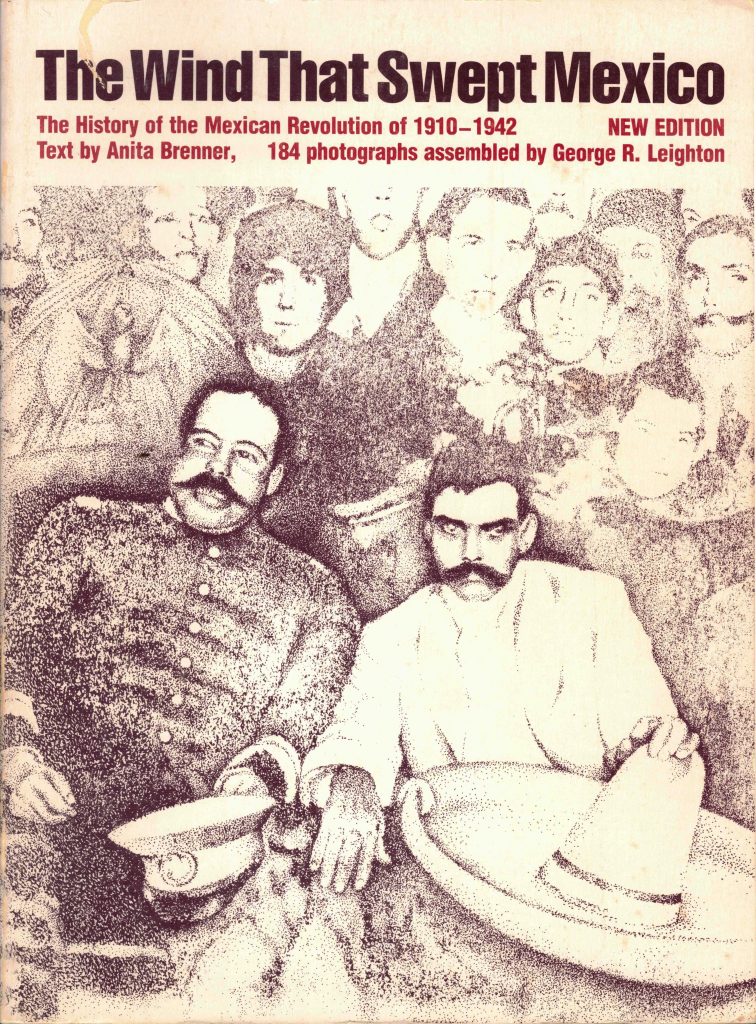

The Wind That Swept Mexico: The History of the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1942, by Anita Brenner, with 184 photographs compiled by George R. Leighton

Proponents of revolution—or opponents, for that matter—might soberly consider the course of the Mexican Revolution, the first of the great revolutions of the 20th Century. Like the other revolts in Russia and China, one sees the same arrogant detachment of the rulers from the ruled, the same heart-wrenching poverty in a land laden with every resource people need to thrive, and the same accidents of history and fate which conspired to give birth to what in retrospect can only seem inevitable, foreordained or foredoomed. For we of the United States of America, the upheaval in Mexico is made more difficult to comprehend by our typical disdain for everything taking place below our southern border. (Above our northern, as well; one has to cross oceans for us to pretend to be interested.) Additionally, the names and events of the Mexican Revolution are for most of us living north of the Rio Grande mere unrelated points of history, if we are cognizant of them at all, tiny little beacons of misremembered high school history tests, blinking like radio tower signal lights above low fog, destined only to be engulfed in a haze of forgetfulness if they be noticed at all. Searching beneath the clouds of our ignorance may lead only to learned befuddlement, as we struggle to make sense of unfamiliar names of people and places, and are left with only a residue of (mis)understanding as deep as that enshrined on most tourist postcard pictures.

Fortunately, we are blessed by the torrential poetry of Anita Brenner’s extended essay upon the Mexican Revolution, which is accompanied by almost two hundred contemporary photographs, in The Wind That Swept Mexico. This book, originally published in 1943 during World War II, provided this particular reader with an excellent place to start learning about this revolt that most in the U.S. are almost entirely ignorant of, and that most Mexicans—I suspect—take for granted. Ms. Brenner writes of her subject with a felicity all too rarely seen, moving through her material with confidence and understanding, showing a sympathy both for the plight of the poor working poor as well as for the thorny difficulties of the actual world of politics. Though her liberal allegiances are always evident, she does not allow herself to be encumbered with cynicism, and though she moves quickly through three decades of tightly packed history, she never rushes and never lectures.

Instead, Anita Brenner shows herself a true poet, inspired by love of her subject, the Mexico she lived in for most of her life. Almost every paragraph presents some jewel of language to the reader, as when she describes one nonentity who became President of Mexico as having “the personality of a ship’s purser”. Or when speaking of German interference in the 1940 Mexican elections: “The Nazis detailed agents, blondes, and money to campaign in both camps.” And yet her poetic language remains rooted in reality, revealing the often harsh ability of moneyed interests to somehow oppress the already oppressed still further.

In the long run, it was thought, industry would solve everything. By its mere existence it would create national prosperity that would sift down to the middle class, that is, the ten or fifteen percent who were considered really people. Work would accrue to the rest, and thus the golden cycle would remain continually in motion.

But the process by which wealth was to sift down, reversing its ancient habits of traveling up, had not yet occurred. Instead, another process had been going on—a process of suction. Through it, the peasants—more than three-fourths of the population—had been stripped of land by laws which gave the hacendados more leeway for expansion, more water, more cheap labor. Many village and tribal holdings had been handed over, and most of the public lands, to great concessionaires, often with subsidies. Occupants who resisted being thus reduced to peonage were shanghaied into the army, or sold to work in the tropics, or sent to their graves.

Anita Brenner puts paid to the idea of ‘trickle-down economics’ long before the days of Reagan and David Stockman

I am sure there are more detailed and pedantic histories of the intricacies of the Mexican Revolution; Ms. Brenner’s essay is merely an précis. And I am not going to recite the many ups and downs and twists and turns and surges forwards and backwards of the Revolution’s course. I won’t chronicle the strong though aging hand of Porfirio Díaz on the Mexican nation in 1910, the fighting in Juarez in 1911, the “Tragic Ten Days” in Mexico City which saw the ascension of Huerta, the stark pleas for land from the Zapatistas, the various campaigns of Villa and Obregón against the government and (sometimes) against each other, nor the pendulum swings of the various post-Revolutionary administrations between lip service to the ideals of youth and kowtowing to landed and moneyed interests (and, always, the United States). No, I will not recite those and other events. That is what Anita Brenner does in her book, and does incredibly well.

Every home was in a state of siege. Civilians dodging out for food were often caught in crossfires, and their bodies lay in the streets. Women ran on desperate errands carrying white flags made of sheets tied to brooms. The capital was paralyzed. A million people had become only a battlefield.

“The Tragic Ten Days” during which the first Revolutionary president and anti-Revolutionary forces inside his own government fought for control of Mexico City

The joy of reading this book does not obviate the tragic and bloody history it recounts. Political enemies are murdered, promises are broken, reactionaries win … and yet somehow progress is made, little by slow, for the poorest of the poor, the downtrodden men and women and children who actually make up the Mexican nation. Brenner obviously sympathizes with the ‘little guy’ against the big combines, the big ranchers, the big money, and the big grafters, but she is canny enough to see and tell the difficult choices forced upon the succession of men who sit in the Presidential Chair of Mexico. She unmasks the money behind this would-be throne, but also is savvy to the Communist influence behind the modern Mexican labor union, the CTM.

The revolutionary chiefs … were eager to pay for their power (and the fat rewards thereof) with revolutionary works. Even those who were mere robber barons were as sincere participants in the new credos as the crusader knights who devoutly portioned their Moorish loot with the Church. So any man who had a good idea and who got it listened to by a general or an important politician had the chance to try it out, or made the chance himself. Ideas in progress ranged from irrigation plans to free breakfasts in the schools to serum laboratories and baby clinics and wall newspapers and beggars’ hostels and art for the people and cheap editions of Plutarch.

Lip service sometimes resulted in actual benefits to the people, and always benefited those on top … while they were on top

(My ellipses, in both cases)

Perhaps the Mexican Revolution was spared the tarring and sneering which met the Russian outbreak a few years later simply because the people of the United States have long accustomed themselves to not give a fig for the politics of Mexico or any Latin American country. While the powers-that-be fretted over the possible importation of radical ideas from Bolsheviki in the Urals and points east, no corporations feared any philosophical import from Mexico, only nationalization of ‘our’ oil fields and ‘our’ mines. Thus those powers ignored the actual examples of socialist ideas only slightly south of the border for fears of the same Commies that Hitler railed against in his appeals to the money men of Germany. As Brenner points out, however, the nations south of Mexico were all very aware of and were inspired by these examples.

The sharpest change was intangible. Fear left the have-nots and was distributed to the haves.

After more than twenty years of revolution, some of its ideals were put into practice by President Lázaro Cárdenas

The pictures which accompany the short text underscore the contradictory distance and nearness of the Mexican Revolution. Some images, especially those of the Porfirio regime and its grand buildings, seem to come from a time almost inconceivably far away, though you can visit Chapultepac Castle today and see the imposing building from which the presidents of Mexico once could look down, quite literally, upon the people of Mexico City. Where once Pancho Villa and Zapata lounged in the seat of the president, now the Museo Nacional de Historia displays murals of the Revolution—as well as the original Mexican Revolution of 181o. But in the photographs of the farmers and families fighting and suffering, the child soldier draped in bandoleras filled with rifle cartridges, and dead bodies lying on the ground after battle or brutal murder, in those pictures we can see all too clearly our present, where the hungry stay hungry, and everyone ignores the rats gnawing at our fingers.

all but a fraction of the total wealth was held by about three per cent of the people. The bulk was held by less than one percent, and most of that was in absentee foreign hands. The economic pump was making wealth flow outward, leaving behind a sediment only; and what came in, to multiply, again flowed outward. The dangerously unbalanced distribution of the means to live and produce—which wherever it occurs has always led to oppression and social explosion—had again for at least ninety-five per cent of the people of Mexico an extra taste of wormwood. There was this byword: “Mexico—mother of foreigners, stepmother of Mexicans.”

The situation under the rule of Porfirio Díaz

There is much talk currently of revolution, and it is a historical truism since the twin poles of the American and French Revolutions that there has always been more talk than actual revolt. For which we may be, perhaps, somewhat grateful. Even before the Mexican Revolution really got going there was much talk amongst Mexicans about revolution, harkening back to the glorious overthrow of the hated Spanish starting in 1810. And the French have never stopped talking of revolution, though the abortive experiments of 1830, 1848, and 1870 might have silenced most folk. Perhaps because of the history of the revolution in France, the Mexican intellectuals of the early 20th Century held fast to the belief that revolutions only occur when nations cannot pay their bills—with the corollary being that, since Mexico was quite solvent, it had nothing to fear from that quarter. Though, as events were to prove, much blood was still to be shed, since money jingling in the pocket can only offend those whose pockets carry only holes.

The battleground was everywhere, and every inhabitant became accustomed to living provisionally, and to being ready to migrate fast, in the wake of one army or away from another, to get food. There were nearly two hundred kinds of worthless paper money.

The joys of revolution, after the convention in Aguascalientes fails to bring rapprochement between the various fighting factions

But, as anyone who has studied the history of revolutions knows, such tumult brings with it much devastation even when the desired changes arrive on schedule. It is not only feelings that are hurt in the process. Fans of Che Guevara must elide over his personal involvement with hundreds, thousands of murders in the name of the new state after the seizure of power in Cuba. The events which left the stirring “Marseillaise” also left the drowned bodies of counterrevolutionaries at the bottom of many French rivers in the ghastly noyades, not to mention that obvious symbol of the French Revolution, the guillotine. And the story of the Mexican Revolution has its share of death and depredation. But it also led to real change in the lives of the most lowly, even if sometimes such change seemed impossible, as Anita Brenner points out.

A study of wages and living standards was made, and the results embodied in a minimum wage law. In most cases the wages declared necessary by the panel of economists, physicians, and social scientists who made the survey were so far above what was being paid that little attempt was made to enforce the law. For the peasants, the list of essentials to life, beginning with eighteen hundred calories and four vitamins, and including a pair of blankets and perhaps one medical visit a year, added up, against what they had, to sheer fantasy.

Plus c’est la même chose, plus ça change

This strange balancing act, or perhaps more an exercise in plate spinning by the various Mexican politicians, this radical yet reactionary ‘two steps forward, one step back’ history is what Anita Brenner tells so well. A child living in Mexico when the Revolution began, her interest in the history is nurtured her obvious and real love of Mexico itself, in all its splendor and problems. She deftly but firmly points out that the real danger to monied interests is for unmonied people to get to know one another, to learn about each other.

Americans and Mexicans, who had known each other, dubiously, only through the dealings of carpetbaggers and the resulting quarrels of the two governments, met by the thousand as individuals, and found each other childlike but nice.

Yet another reason to avoid fraternization

Written under the influence of a global conflict whose outcome was then still very much in doubt, and at a time when many of those who had participated in the Mexican Revolution—those, that is, who had not been killed in battle or murdered—were still actively engaged in the politics of the nation, this book may not, cannot, be the final word on the Mexican Revolution. And much more was still to come, as the PRI (originally the PNR of Calles and then the PRM of the much-beloved Cárdenas) shifted through the sands of time down to the eventual loss of power in 2000. But what Ms. Brenner’s book may lack in completeness and academic rigor it more than makes up in immediacy and poetic vigor. She writes, as she tells it, of an ongoing revolution, of a Mexico still in the process of creating itself. And she pleads for greater understanding of the winds buffeting our neighbor to the south, underlining the point that the United States and Mexico have opportunities for greater understanding and greater cooperation, as well as threats to both countries from continued ignorance.

The opportunities are still there. As is the ignorance.

[The Mexicans] fear being cheated, through our domination, of what was achieved by the million lives given up in the revolution. Our record, after all, has been, there and in other Latin American countries, to strengthen those who gain by strangling the Four Freedoms.

Ms. Brenner points out the rational reasons for suspicion of the United States

Detail from El Feudalismo Porfirista, by Juan O’Gorman, 1970-1973, on display at the Museo Nacional de Historia in Mexico City