Simon The Jester, by William J. Locke

Most will be familiar with the “Uncanny Valley” concept in robotics and computer animation, the hypothesis being that as the designed object nears more closely an actual human being a point is reached at which the resemblance is so near as to call up emotional responses, yet the distance between the created object and its real exemplar is still such that those responses will be eery distaste or confusion or off-putting weirdness. That this idea is merely a hypothesis with little or no scientific basis may be seen in the fact that the crowds of people (back when there were crowds) attending premieres of Marvel movies did not flee screaming from the theater in revulsion at the counterfeit humanity depicted therein.

But since we human beings are story-making, explanation seeking, pattern seeing animals, may I be permitted to posit a similar idea as pertains to works of literature? For I believe I have just experienced something like the “uncanny valley” as I finished an old (over a century old, as it was published in 1909) novel by a once-popular writer, the book Simon The Jester by William J. Locke. I found it to be a perfect novel, with perfect characters, perfect observations, perfect dialogue … up to a point. And at that point, something strange happened, and I had an out-of-novel experience which left me disoriented and nonplussed by the very book which up to its closing pages had seemed a rare work of genius, but now became a burlesque grotesquerie, an incomprehensible jamais vu construction that left me shaken and somewhat sorrowful. Call it the Uncanny Asymptote of Nearly Perfect Fiction.

On a murky, sullen November day Murglebed exhibits unimagined horrors of scenic depravity. It snarls at you malignantly. It is like a bit of waste land in Gehenna. There is a lowering, soap-sudsy thing a mile away from the more or less dry land which local ignorance and superstition call the sea. The interim is mud—oozy, brown, malevolent mud. Sometimes it seems to heave as if with the myriad bodies of slimy crawling eels and worms and snakes. A few foul boats lie buried in it.

Here and there, on land, a surly inhabitant spits into it. If you address him he snorts at you unintelligibly. If you turn your back tot he sea you are met by a prospect of unimagined despair. There are no trees. The country is flat and barren. A dismal creek runs miles inland—an estuary fed by the River Murgle. A few battered cottages, a general shop, a couple of low pubic-houses, and three perky red-brick villas all in a row form the city, or town, or village, or what you will, of Murglebed-on-Sea.

A fine description of a depraved landscape

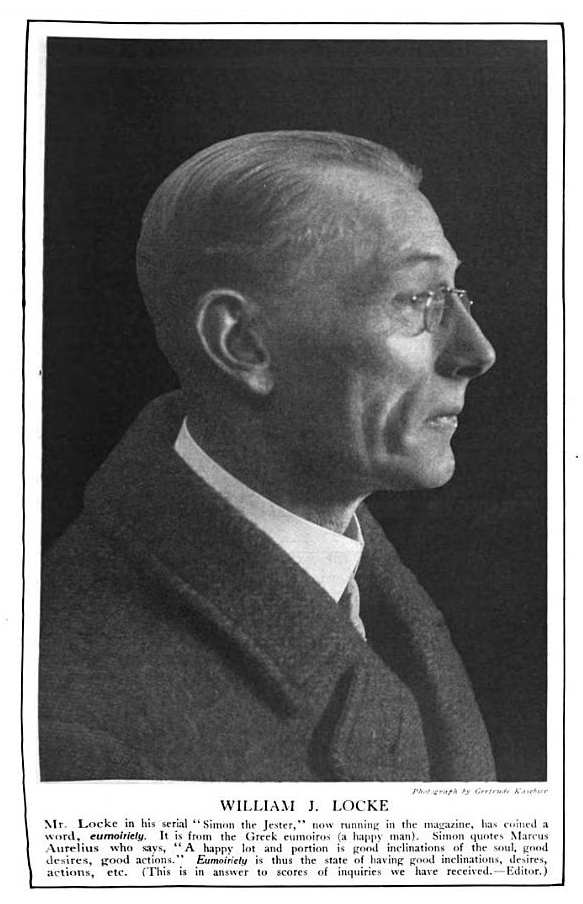

Simon The Jester begins with the titular Simon de Gex, M.P., seeking the most God-forsaken place in all England, in which quest he is successful. He hies himself to this most baleful clime, there to dedicate himself to a life founded upon the principles of Marcus Aurelius, specifically to be a “happy man” by his devotion to “good inclinations of the soul, good desires, good actions.” Simon calls this concept ‘eumoiriety’, based on the Greek word translated above as “happy man”, εὒμοιρος. The neologism is not entirely euphonious, and its continual appearance is perhaps the one discordant element in the novel’s first two hundred and fifty pages, and indeed its appearance was so perplexing to Mr. Locke’s initial readers that a special note was added to a subsequent issue of the magazine in which the first episode of the novel was serialized, explaining the unfamiliar (and now quite reasonably forgotten) term.

Simon has deep reasons for seeking a state of … ahem … ‘eumoiriety’, which I shall leave for the reader to discover for him- or herself. Though it seems that he should be quite content with his very fortunate life, in which he occupies one of the highest places in the great pyramid of being which is the British Empire in the first decade of the 20th Century, he suddenly jumps his tracks and leaves all his previous ruts, and of the adventures which follow this novel is constructed.

“These things are no one’s fault,” I said gently. But just as I was beginning to console her with what thumb-marked scraps of platitude I could collect—the only philosophy after all, such is the futility of systems, adequate to the deep issues of life—the door opened and the manager announced that the police had arrived.

Simon de Get is a true and wise philosopher, in spite of everything that happens

And what adventures they are. Recounted in wry and urbane reflections as a strange new world opens up before him, our Member of Parliament seeks to do good deeds, the first of which he sets himself is to remove his politic assistant Dale Kynnersley from the clutches of a gold-digging lion tamer, the fascinating Lola Brandt. But when he visits the femme fatale, Simon is peculiarly struck by the strangeness of her environs, her person, and her friend, the dwarf Anastasius Papadopoulos. This last strange figure trains cats—ordinary housecats—in feats of derring-do and mastery just as Lola once was mistress to a pride of trained lions.

The intersection of Simon’s world of privilege and wit with the demimonde of Lola and Professor Papadopoulos drives the novel into some strange and romantic places, though most of the action in Simon The Jester are the merest trifles. However, as Alexander Pope said, “Trifles themselves are elegant in him,” and that poet might have used Simon de Gex as the very model for this sentiment. For every page of Locke’s novel scintillates with sharp intelligence and trenchant insights. His narrator is the best of a rare breed, the true aristocrat, in the original sense of that word first needed Ancient Greece. Could such fine patriarchal British aristocrats have ever existed? One can only hope.

She looked straight in front of her, with parted lips, fingering her handkerchief and evidently pondering the entirely new suggestion. I thought it best to let her ponder. As a general rule, people will do anything in the world rather than think; so, when one sees a human being wrapped in thought, one ought to regard wilful disturbance of the process as sacrilege.

So courteous is de Gex that he will not interrupt even a silent woman

Simon The Jester is a novel I only read by accident, as it came to me as an unwanted (and unwonted) gift from a friend who that I “had a lot of books” and so naturally thought of me when she was getting rid of some old books. Besides the fact that I don’t read much in the way of hundred-year-old popular fiction, it also belongs to a genre I am hardly acquainted with, the romance. (The version I was gifted with includes as well four nice illustrations by James Montgomery Flagg, known today for creating Uncle Sam’s famous “I Want You!” poster.) But the suasive power of Locke’s beautiful language is remarkable, as each remark by the protagonist reveals a fine sense of propriety (in the best sense) and a very real understanding of the human condition.

In this age of flippancy and scepticism, if a human soul proclaims sincerely its faith in the divinity of a rabbit, in God’s name don’t disturb it. It is something whereto to refer his aspirations, his resolves; it is a court of arbitration, at the lowest, for his spiritual disputes; and the rabbit will be as effective an oracle as any other. For are not all religions but the strivings of the spirit towards crystallisation at some point outside the environment of passions and appetites which is the flesh, so that it can work untrammelled: and are not all gods but the accidental forms, conditioned by circumstance, which this crystallisation takes? All gods in their anthropo-, helio-, thero-, or what-not-morphic forms are false; but, on the other hand, all gods in their spiritual essence are true.

Deep thinking in a light trifle

And the sparkling insights of Simon accompany a pell-mell rush across colorful vistas of incident and romance, a journey through a world that is no more, and likely never was. Yet throughout the novel, Mr. Locke manages to make the most bizarre situations compelling fiction. Each crazed scene is more believable, more true than the last, until … until it is not.

And so we come to my crux with this novel, or perhaps with my reading. I have elided over most of the plot because Simon The Jester is worth reading on its own terms, and Locke provides continual surprise in his fine writing. But at some point very close to the end of the book, I became disengaged from the narrative world I’d effortlessly inhabited for the 250 or so prior pages. I can only liken it to an experience I had once of watching Terry Gilliam’s Brazil on network television, during the viewing of which I had become totally transfixed by the almost miraculous depiction of another world that is also our own, only to be shaken out of my dark reverie by the intrusion of an ad for foot odor products (or something like that). And though the poignant episodes of the last third of the book were some of the truest I have ever read of a man learning to care deeply for his fellow human beings, at some point the lines holding me tightly to the story slipped their moorings, or I slipped mine, and the end of the book slipped away from me like a bucket dropped down a well.

“Well, I’m damned!” said I, in my native tongue.

I don’t often use strong language; but the occasion warranted it. I was flabbergasted, bewildered, outraged, humiliated, delighted, incredulous, and generally turned topsy-turvy. In conversation one has no time for so minute an analysis of one’s feelings. I therefore summed them up in the only word.

Strong language indeed from our narrator

The question I have asked myself since completing this novel is whether the problem I found is within the book, or within myself. And I confess I have no final answer. As I say, I do not read romances as a rule, and perhaps my disdain for the novel’s climax is a dislike for the resolution of the romantic triangle. (There’s always a triangle.) However, I studied the idea of using the other leg of the triangle as the result, and am not sure that I should have liked that any better. It is also possible that Mr. Locke simply constructed a puzzle for which either solution was unacceptable—though as before, I cannot say whether ‘twould be unacceptable objectively, or to myself only. I leave the entire matter as a problem for the reader, telling you up front that I have no idea of the solution, if solution there be.

It is not so much the thing that is done or the thing that is said that matters, but the way of doing or saying it. In the commonplace pat on the hand, in the break in the commonplace words there was something that went straight to my heart. I squeezed her arm and whispered:

“Thank you, dear.”

Still, the language of this book—trifle though it be—is so excellent, so powerful, that it succeeds even where I may perceive some small failings at the end. So I cannot recommend Simon The Jester wholeheartedly, nor can I recommend it highly enough. William J. Locke is a fantastic writer, famous for what it’s worth in his own time. And his is a century-old voice well worth listening to. I’ll report after I read another of his novels, which I shall.

Leave a comment