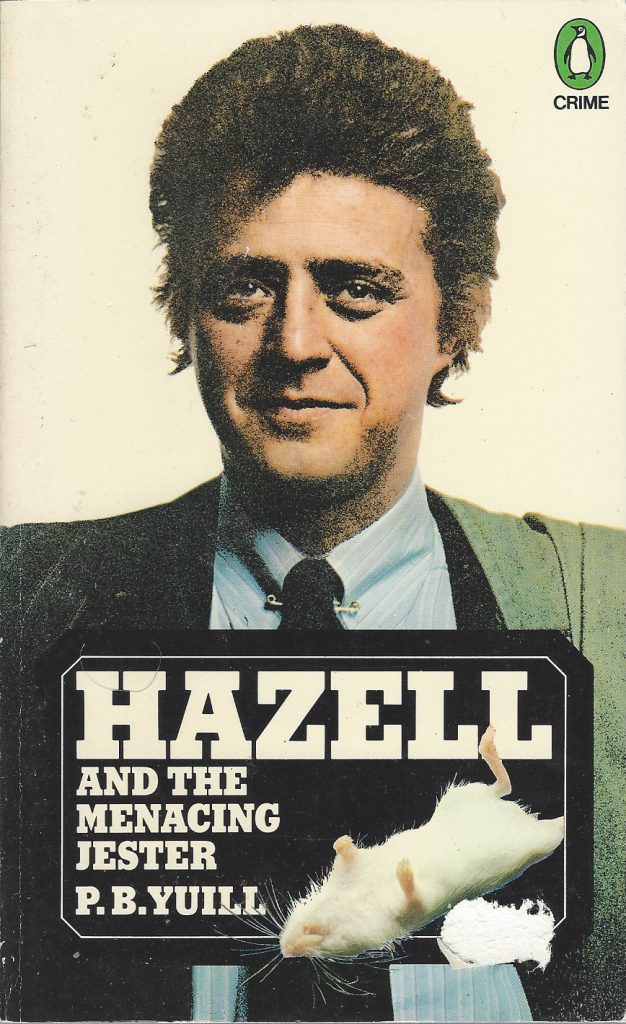

Hazell and the Menacing Jester, by P. B. Yuill [Gordon Williams & Terry Venables]

I like reading books. Really, I do. I read for enjoyment, to learn stuff, to delay the inevitable minute when I have to return to work, and to distract myself when I’m sitting in the meditation chamber in my house. And I am continually amazed at the talented people who think the ideas and write the words and fill the pages in the books I read. Kudos to each and every one. Even the ones I report negatively on; hey, you still got published. And occasionally, very rarely, I read a book that underscores the staggering incident which occurred 50,000 years ago (give or take) when human brains developed some strange quirk of consciousness that enabled the invention of the most amazing thing in the entire galaxy—nay! in the entire universe! I speak, of course, of language.

Okay, okay. You’re right. I kind of lost it there. Unfortunately, I am not one of those talented people who can use this almost unbelievable tool we take for granted to transmit information and ideas to my readers. I realize it’s a struggle to read my words, and that makes me all the more impressed and beholden and blown away by those creative writers who go beyond just being staggeringly great and who use language in a way that makes it clear to their readers just how blessed we all are to have words and grammar and all that panoply of language that can be written and printed into little blocks of paper that used to cost a mere sixty pence and which now go for eight, nine, ten bucks at the airport or for next to nothing at the library book sale. (I’m talking about books.) Whatever the cost in mere money, the gift of certain writers is to use words in exciting ways that remind us just what a powerful gift we’ve been given by our long-ago forebears, whether evolutionary or biblical. The tripping creativity of Alan Burt Akers is why I love his Dray Prescot series, when I know in my heart of hearts that I should not. The words and what the man does with and to them is why I revere Stanislaw Lem, and followed his suggestion as to which science fiction writer to read (though I still wonder how much of his innovative wordplay came from his translators, and how much came in spite of them). Her searing mastery of modern speech and her perfect voice is what made me love Cintra Wilson’s Caligula. And now I come—late to the party—to P. B. Yuill.

In James Hazell, a private detective of distinctly working class London roots, the pseudonymous author P. B. Yuill has created one of the most engaging, delightful, human, and (mostly) humane characters ever seen in fiction, certainly in mystery fiction. Unlike the ever-brooding Marlowe, Hazell seems almost to enjoy life, even as he wistfully watches the London he loves being replaced block by block in favor of flash spivs and their money. More than this, he is an authentic Cockney character in a world saying ‘goodbye’ to neighbors, neighborhoods, and neighborliness. In contrast to most of the people he meets in Hazell and the Menacing Jester, Jim Hazell is genuinely interested in everything around him, and while he is perhaps not the most clueful detective (or person, for that matter) at all times, he is as dogged as Churchill was supposed to be, which may be a better asset for a private eye than mere robotic ratiocination.

Hiding behind the P. B. Yuill name on the cover are Gordon Williams, a Scottish author become Londoner, and Terry Venables, an English footballer with a long-storied career both on the pitch and on the sidelines. I assume that Venables supplied much of the ‘real’ London in this book, especially the never-ending flood of wonderful Cockney rhyming slang—but I may just be underestimating how much a trained journalist can pick up by hanging out in the right pubs. In any event, the partnership between the two began in 1972 with a sports novel (under their own names), They Used To Play On Grass. There must have been some magic there, for they collaborated on three novels featuring the blue-collar James Hazell under the P. B. Yuill nom de plume.* Unfortunately, I started with the third book in the series, the subject of this review. Also unfortunately, there are only two more books in the series. On the other hand, I am grateful that there are two more, and have already ordered them from the UK.

I really cannot express adequately how wonderful the language of this book is. Indeed, any words I use simply pale beside the inventive words and images of the novel. From the very beginning right through to the last page, the first person narrative of Jim Hazell as he recounts this puzzling case warms the heart and delights the ear. However, like me, it isn’t always clear what Jim is saying. Unlike me, however, this is a fault of the reader, not the author. The language of The Menacing Jester is so full of slang that I am sure I would have understood it less had I read it when it was originally published almost fifty years ago, because now I can fill the holes in my deficient knowledge of British slang by looking up problem words on the Webbertubes, at least when the meaning isn’t clear from the context. (Even I was able to piece together—once I’d gotten used to the basic premise of rhyming slang—that getting kicked in the Niagaras meant he’d been kicked in the balls (“Niagara Falls” = “balls”).) But this book isn’t just some slapping together of odds and ends from a slang dictionary; P. B. Yuill turns out to be quite a creative fellow. Check out the very opening paragraph of the book:

Moneybags Beevers and his weird little problem first cropped up on a wet Thursday morning in May. I was just back in the office after flu. Outside it was raining knives and forks. I felt about merry as him on the slab with the big-toe label.

Nothing too difficult to follow there. Apparently the Welsh say “raining knives and forks”, in Welsh, one supposes. But those sentences sing, really sing. And even I could understand the first rhyming slang a couple of paragraphs later on the same first page:

I sat there fighting off the day’s first fag. My new black brogues were damp. Bargain shoes, always a mistake. Soon as I got a few quid indoors it was down to Bond Street for a pair of handmades.

The ashtray was still full from last week. It looked revolting. Soon as I got a few quid ahead of the game I’d be puffing six-inch Havanas to go with my St Louis Blues from Bond Street.

Good shoe philosophy

By the way, if you’re going to have a problem with ‘fag’ as a term for cigarette, you really shouldn’t read a book where every black person is called a ‘spade’. That’s about as close to a Trigger Warning as this book needs, unless you cannot stomach novels with violent fight scenes, in which case you probably want to avoid most of the mystery genre.

Now, I occasionally read a book in French, both to keep my hand in and also to remind myself that I really need to study French. And, depending on the book, I’ll need to consult a French-English dictionary for this or that term. If I’m reading something fairly old, I usually don’t have to look up more than a few words every dozen pages; if I am reading Simenon, I just use the dictionary to prop up the book since I’m going to be consulting it often. I don’t even bother with modern fiction with a lot of slang; that kind of depression I don’t need. Well, reading this book is certainly possible without knowing all the various Cockney rhyming slang, as well as the other British slang or specialized uses of specialized terms†—even I could figure out that taking a butcher’s at something meant taking a look at it. But it did help to be able to look up these terms online, although I still am not entirely clear what was meant by someone’s frizzy hair keeping snow off the cabbages, unless that’s just the obvious. Anyway, I ended up looking up quite a few new slang phrases, so many that I have decided to create a Cockney Rhyming Slang page for my blog, as I learned so many wonderful new terms that they’d entirely overwhelm my Friday Vocabulary posts for months to come if I tried to sneak them in there. (I’ll sneak back here and update this post with a link to the Rhyming Slang page once that’s ready.) And here’s the link to my Cockney Rhyming and other British Slang page.

So, let’s see … six paragraphs—more or less—about the book, and I haven’t even begun talking about the story. Well, it’s a doozy, with lots of twists and turns, characters both repulsive and alluring, and one of the best fight scenes I have ever read. If you’re the type who needs a synopsis before you’ll even pick up a book I’ll say that Mr. Beevers is being terrorized by someone whose malicious practical jokes have a sinister purpose. (Yeah, that’s right. The novel doesn’t even start off with a murder in the first thirty pages.) But the already engaging story about the slightly bent Mr. Beevers and his more smarmy partner is made truly magical by the lilting spin given it by Jim Hazell; reading The Menacing Jester we can almost imagine we’re being regaled with the tale at the world’s best corner bar, and Hazell comes off as a man we’d love to bend an elbow with.

Along the way we are led by our author(s) on a tour of the real capital city of post-swinging England, a tour that takes us from penthouse apartments to fabled Wembley, with many stops along the way to deal with hangers-on and the unwashed masses. The masses come off much better, on the whole, than the toffs and spivs who look down upon them. I have only been a tourist in London, so I don’t have the nostalgia for a time forgot that might be the book’s effect on those who have lived or even grown up in that city central to Britain. But there is a homesick tinge to the vibrant charge running through the entire book, and many of P. B. Yuill’s trenchant commentaries on society seem like they could have been made last week.

She had all the trendy ideas, men were destructive, society was polluting itself to death, our food was poisoned, war was coming in two minutes and our only hope was to kneel in front of hairy gurus from caves in India and find inner harmony.

Even in our app-filled age, some trendy ideas have more staying power

Really, I meant it so many words ago when I noted that my own words were not adequate to convey how terrifically good this book is. Is there something about the Cockney life that engenders such poetry in speech and prose? Perhaps a magic in the pints and The Pinch? There are bottles of amber fluid the world over, but wordsmithery of this exceptional quality is a rare delight. Cynical without being weary, fallible without being egregious, and loyal without being a prig about it, James Hazell is my new favorite detective. I cannot wait to read the first two books in the series, though I also don’t want to finish reading all the books in the series.

* The Interwebs list four books by P. B. Yuill, and usually state that all four are by the above mentioned team of Williams and Venables. However, some of the commentary on the first book published under that pseudonym would indicate that that book, The Bornless Keeper, was written solely by Gordon Williams. In any case, the book does not feature Jim Hazell, and, by the accounts I read on screens emitting light towards my eyes, it is not very good.

† Who knew that ‘Scouse’ was a dialect of Merseyside, or even that there is such a county as Merseyside, and that therefore one might call fans of Everton ‘Scouses’?

Leave a comment