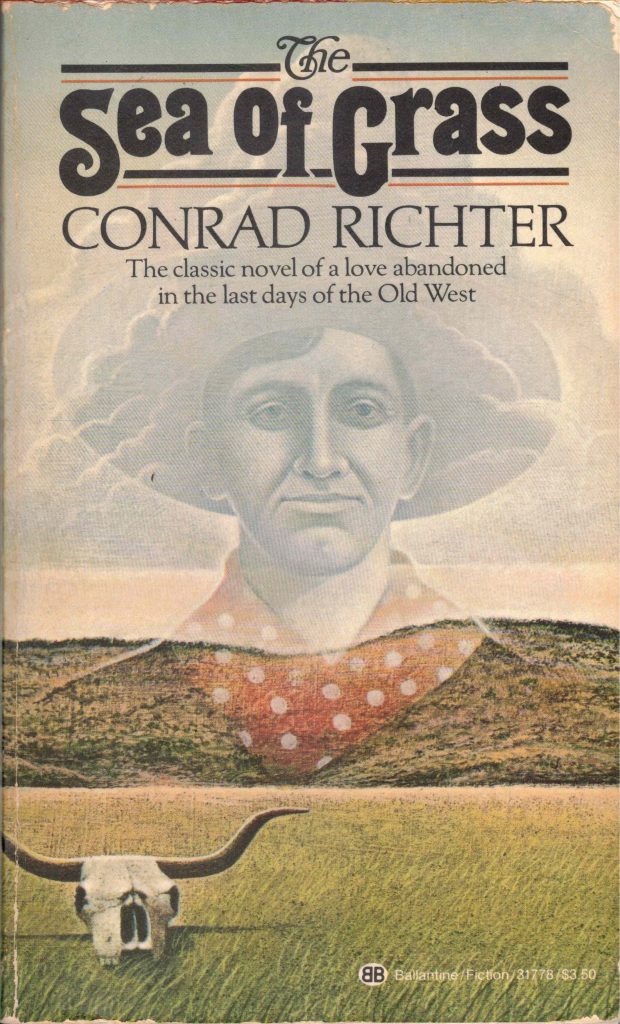

Sea Of Grass, by Conrad Richter (1936)

This very brief (just over a hundred pages, in the edition I read) narrative is a prose poem, a threnody for a lost time and place, New Mexico when it was new in the American imagination. As well, it is a meditation on the mystery of marriage and the ways of men with women. It is also a Western novel mistakenly assigned to schoolchildren, perhaps with the notion that it is short and therefore the little ones might actually complete their assigned reading, or perhaps because the narrator is himself a youth in the opening chapters and thus some identification is expected by the priests and priestesses of pedagogy. The book is mistakenly compared to Zane Grey’s work, about which the less said the better. The author seems to have been yet another example of a man bewitched by the wide open spaces of the Southwest, like the creator of Krazy Kat, though Conrad Richter never personally experienced the lost era he so obviously longs for, although ….

His rude empire is dead and quartered today like a steer on the meat-block, but I still lie in bed at night and see it tossing, pitching, leaping in the golden sunlight of more than fifty years ago, sweeping up to his very door, stretching a hundred and twenty miles north and south along the river, and rolling as far into the sunset as stock could roam

Reading this paean to the now lost days when the great cattle ranches and even greater cattle herds dominated the mythic West, you know that the author truly lived this life he remembers, that he experienced as a young man the unceasing mutability of this ‘sea of grass’. You would be wrong. That is, Conrad Richter only moved to Albuquerque when he was almost forty years old, and you would be wrong if you thought, as did I, that Richter had lived through the last years of the crowd of beeves and antelopes that once rode over thousands of square miles of New Mexico grassland with nary a town, home, or even outbuilding in sight. Such is the poetic power of his language that we can be forgiven this mistake (yes, I forgive myself in this instance), and can almost be persuaded that he speaks of real events and real people reflected in the mirror of memory a half century later. Such is the benison granted to fiction, to make more true than artless nature the vision of other peoples and other times.

To the newcomer in our Southwestern land it seems that the days are very much alike, the same blue sky and unchanging sunshine and endless heat waves rising from the plain. But after he is here a year he learns to distinguish nuances in the weather he would never have noticed under a more violent sky; that one day may be clear enough, and yet some time during the night, without benefit of rain or cloud, a mysterious desert influence sweeps the heavens. And the following morning there is air clearer by half than yesterday, as if freshly rinsed by storm and rain.

Conrad Richter’s Sea Of Grass is like an Icelandic saga writ small upon a landscape writ large. The intricate genealogies and intertwined characters of the sagas are whittled down to only three, four, five actors in the brief drama of this novelette, while the twisted paths leading through the mountains between the narrow fjords of the tiny island of the North are replaced by the most expansive horizons imaginable beneath a hot but nurturing sun. And while the sagas seem always to involve violent action—and often burning—and carefully cultivated hatred, in Sea Of Grass the action is nuanced and often ‘offstage’, the emotional turmoil only guessed at for every character save the memorializing narrator. At the heart of the story is the helpless love of Colonel Brewton for the lovely Lutie from St. Louis, the lord of cattlemen hopeless before the strange female power of the woman who detests the large and lonely land from which the Colonel’s own power derives. Lutie turns heads wherever she appears, including that of our narrator, Colonel Brewton’s nephew, Hal. A dark and unspoken shadow lies between Lutie and her husband, a shadow which reflects the clash between the Colonel and the new district attorney Brice Chamberlain. The up and coming lawyer means to break up the endless ranch of the Bar B brand—the Brewton brand—and to support the ‘nesters’, immigrants who seek to turn the ‘sea of grass’ of the title into farmland. With deft strokes Richter limns the clash between Brewton and Chamberlain, and this almost stream-of-consciousness narrative shows the collapse into desuetude and decay of the empire of cattle giants under a misguided idea of progress.

Written in 1936, this dirge for the Southwestern grasslands may have been influenced by the ecological disaster underway at the time, that devastation of the soil we now call “The Dust Bowl”. And it is true that much of the western United States is better grassland than farmland. But the king of New Mexico beeves that Richter portrays in Sea Of Grass owes more to a devotion to strong men than to ecological, economic, or even Western history. (Clashes between cowmen and farmers, or the related dust-ups between the cattle ranchers and sheepherders, rarely ended up only in the courtroom, and at times erupted into full-scale war.) But Richter has created an almost godlike father figure doomed to fall into tragedy, just as all fathers must eventually be revealed to have feet of clay. Here the tragedy, in all its aspects—the Colonel’s marriage, the fights between ranch and farm, between country and city—the tragedy is visited upon and fulfilled by the youngest son of Colonel and Mrs. Brewton, Brock. Spoiled and erring, Brock sneers at the Brewton name and its import, and the young man’s fate ties together the dark threads of the story in a heartrending climax to this elegy of the old west and the towering figures that once rode across the vast plains as their rightful dominion, only to subside once more under the waves of time.

I believe now that every piece of news about Brock my uncle read in the Albuquerque and Denver papers was a secret Apache lance in his heart. His forehead was incommunicable as an old rawhide and branded like one with the mark of the band of his hat. And of what went on behind it he never spoke.

The prose of Sea Of Grass has been compared to that of Zane Grey’s Riders Of The Purple Sage, but that is to compare poetry with doggerel. Richter’s genius is to present a poetry of just those men and women who never speak their innermost truths, but live them in their every act and choice. The first-person narrative of Hal flows true and natural through this book like a burbling brook in spring, and his memory of his uncle and Lutie evokes clearly their deep character and the sway they still have upon him years later. But it is the silences that Richter somehow manages to convey in his writing, the unknowableness of the inner life of the two main protagonists of the novel and their secret thoughts over all that came between them. And the flowing narrative with its sparse dialogue also conjures up just the sort of inner monologue a man used to riding for miles across an endless land beneath an infinite sky might have. Some loves are not made stronger by talking about them, but by living inside them and through them and, at times, in spite of them.