The Lies That Bind, by Kate Carlisle (A Bibliophile Mystery, #3 in the series)

Kate Carlisle is no Raymond Chandler, and her book—The Lies That Bind—is an affront to his project of raising mystery fiction to the level of literature. If anything, the author of this, the third in the series of so-called ‘Bibliophile Mysteries’, has lowered the standards of literary detection to that of the most vanilla romance novel, wherein the girl gets the man in spite of the seeming obstacles, which in this case means that two murders and as many brutal assaults are merely McGuffins to distract us from the foregone conclusion of ‘Will She or Won’t She?’ She will, though any steamy action will take place offstage or in the reader’s imagination, which is hopefully more fecund and more suasive than that of our author.

Alice kept turning and bucking, fighting to get Minka off her back, but it was like trying to remove a giant tick. Minka wasn’t letting go.

Girl-on-girl action turns into mere horseplay through poor wordplay

Ms. Carlisle’s crimes against the written word are many, but most have been reclassified as mere misdemeanors in the post-PC age, where typos are ascribed to thumb typing and grammatical mistakes are blamed upon autocorrect. Perhaps better editing might have averted some of the most galling errors, but the same may be said of today’s most literary and literate works; editors long ago were deemed non-essential personnel, and vanished and almost forgotten is the heyday of the formidable editors who trained and shaped rough writers into greatness—titans such as Max Perkins and Joan Kahn. But the flaws are many, and the only thing that stands out in her novel is the shallowness of her descriptions, characters, and plot.

This was only the second evening of class but the group was already beginning to meld nicely. As everyone worked, the personalities of some of the students rose to the fore. I’d like to think we were all getting used to each other’s quirks and foibles, but some were more easy to acclimate to than others.

Cynthia and Tom, for instance, tended to bicker quietly over almost anything. The subject matter could be as trivial as the choice of covers for the books they were making. ….

Gina and Whitney liked to talk, too, but at least they were entertaining. Both were pop-culture fanatics and proud of it. They told me what they’d seen on TMZ the previous night; then Gina showed everyone the GoFugYourself.com app on her phone. Kylie and Marianne both begged to see the latest red-carpet disasters.

Mitchell was a jovial man, cheerful and interested in the others’ lives. Dale, Bobby, and Jennifer, on the other hand, worked quietly and kept to themselves.

When Alice wasn’t texting her boyfriend, Stuart, or rushing off to the bathroom, she would absently rub her stomach while she worked. Fortunately, she was blessed with a self-deprecating sense of humor, so most of the students found her charming, despite her health issues.

Personalities, quirks, and foibles—Oh, My!

Kate Carlisle, or at least her narrator, the inharmoniously named Brooklyn Wainwright evince a boutique view of reality. (Do not worry, dear reader, there will be an explanation, a lengthy explanation, for that unusual and ‘kicky’ name.) In this worldview, apparently formed by attending gallery openings and purchasing the handiwork of one’s friends, every craft shop opening is a triumph, a splendid success for creative types who never need worry about supply chains and customer service, nor fret over upcoming rent payments after weeks of empty showrooms populated only by occasional ‘Just looking’ customers and the sullen teen watching the cash register whenever she is not watching her phone. Add to these scenes the fact that the action (if one may call it that) in this novel (ditto) is set in San Francisco, where the only thing higher than the rents are the … no, nothing is higher than the rents in San Francisco. Which makes most of our cute cast of characters like the cast of Friends, living far beyond any visible means of support.

Like many San Francisco neighborhoods, South Park was a mix of chic and charm with a hint of scruffiness around the edges.

Brooklyn knows the charm of the bourgeoisie

Not that the San Francisco of this book is recognizable to anyone who ever lived in The City. Save for a chilly night breeze on the opening page, the weather in this fictional SF is always beautiful, with clear blue skies compared to a painting by François Boucher. Though our protagonist lives in a South of Market factory converted into apartments, with the obligatory lesbian neighbors (sculptors) and the gay couple (chef and hairdresser), she has the understanding of a tourist when it comes to the 49 square miles of San Francisco. For instance, she revels in driving down Lombard Street to clear her head, which has the opposite effect for most SF residents and is done only under extreme duress imposed by visiting family. She parks her car in Union Square to go to Chinatown (which I suppose is one way to avoid the homeless in the ten blocks or so between her apartment and Dragon’s Gate), where she rhapsodizes over the butcher shops in the first two blocks “into the heart of Chinatown”. Um, no.

We walked along the narrow sidewalk, past electronics stores and teahouses and jewelry shops filled with ivory, jade, and amber and thousands of rainbow-colored strands of beads. Souvenir shops hawked every conceivable tchotchke known to man, from ornately beaded silk slippers and wallets in every color to wooden back scratchers, articulated wooden snakes, kites of every shape and size, willowy bird cages, Chinoiserie teapots, jewelry boxes, and delicate eggs on wooden pedestals.

Butcher shops displayed rows of cooked ducks hanging from metal racks, drying in the breeze. Baby bok choy, snow peas, and ruffle-leafed Chinese cabbage filled the vegetable stands in front of the markets. I breathed in the scents of fried wontons and sweet sausage buns and wanted to eat everything I could smell.

Two blocks into the heart of Chinatown, we found the address on Mr. Soo’s business card.

Pro tip for writers doing research online: the meat and produce markets in Chinatown are on the opposite end of Grant Avenue from the Union Square entrance

But this superficial understanding of San Francisco is no great crime. Heck, Steve McQueen in Bullitt managed to find a shortcut from Bernal Heights to Ghirardelli Square which in no way detracted from the best movie car chase of all time. No, it is more the unrelenting nature of the shallowness, the banality of the feeble, which casts this book into a literary black hole from which no interest can escape. Even the putative subject of our bookbinder-cum-detective is described in language better suited for an in-flight magazine than for a narration purporting to describe the narrator’s true vocation and passion. The only passion given to any subject in The Lies That Bind comes when Brooklyn rhapsodizes over food or wine, and even that is not allowed to come between the trite set pieces of ‘action’ and the pallid description and characterization which make up the bulk of this ‘novel’.

I swallowed the bite and almost swooned. The buttery ravioli sauce was extraordinary. “Oh, my. I need a moment.”

“It’s rather good, isn’t it?”

As good as it gets, at any rate

But again, none of this rises to the level of felonious abuse of literary license (though the incessant petty infractions of bad writing might call for a hefty fine). Of course her love interest is a suave British former secret service agent, and of course her female bêtes noires are all vile harpies. And naturally Brooklyn herself has as parents a couple of Deadheads who now live on a Sonoma commune run by Guru Bob (I’m not kidding) where the quondam hippies are now all winery millionaires. And though her ‘intuitive’ mother is now learning Wicca, yet cannot remember whether to do “the banishment spell during the full moon or the waxing moon”, such trivial characterization still constitutes no great crime against reading humanity.

And I was not even considering penning another of my futile jeremiads against bad writing whilst struggling to ignore the completely ridiculous plot point around which much of this book supposedly turns. To wit: central to this ‘mystery’ is a rare almost first edition of Oliver Twist, lovingly restored by the protagonist and expert bookbinder, Brooklyn Wainwright. Our narrator is pressured by one of the evil harpies mentioned above not to divulge to prospective buyers that the volume she had brought to scintillating life is not the true first edition, which was not published under Charles Dickens’s name, but under his journalistic pseudonym, ‘Boz’. The restored book, however, has Dickens listed as the author as well as slightly different illustrations, making the volume not worth the tens of thousands it will fetch eventually in the seedy black book market this novel claims to exist. Where to begin? First off, anybody buying this Dickens novel would know exactly what points to look for in a true first edition. Secondly, any amount of restoration to a rare book, no matter how small, drastically decreases its value to a collector (and yes, they can tell)—and this book was given to Brooklyn “in tattered pieces”. And finally—and here we leave the confines of the novel and take a quick glance at the Interwebs, already available when this novel was published in 2010—the Oliver Twist first edition was issued in 3 volumes, meaning that the ‘book’ that drives so much of the plot isn’t even half of the needed McGuffin the author wants it to be. (By the way, you can find very nice copies of the true first edition online for around $10,000 if you’re in the market.)

“Another dead body?” I cried, having officially reached the end of my rope. “What the hell is going on with me? Was I a serial killer in a past life? Why do I keep finding dead people?”

Enough already.

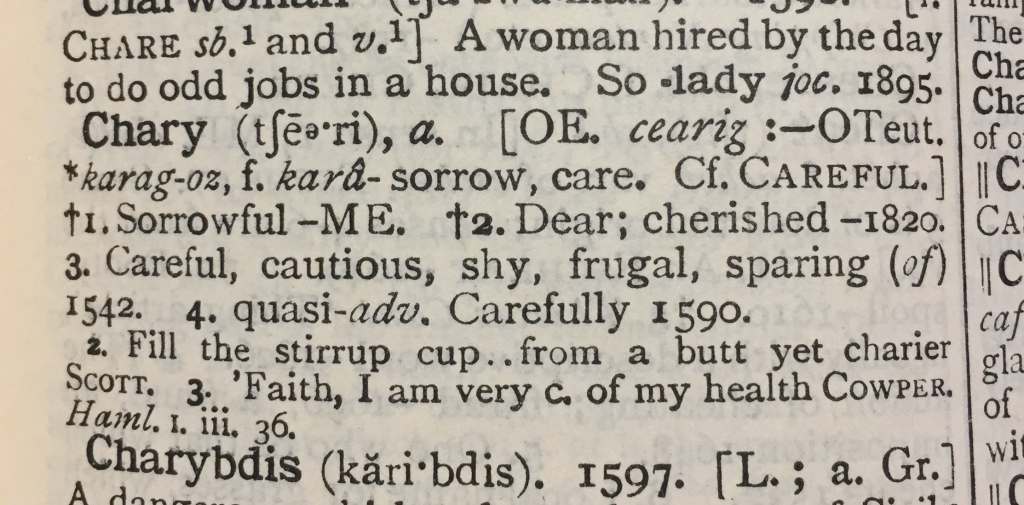

“I agree it’s all become a bit chary,” Derek confessed as he struggled to keep the bookcase suspended.

“Chary? I hope that’s another word for totally unfair and highly annoying.”

“Something like that,” he said, grimacing as he shifted to lower the bookcase.

Strangely enough, ‘totally unfair and highly annoying’ would make a fine subtitle for The Lies That Bind

No, even this basic ignorance of the very subject our heroine is supposed to be expert in was not sufficient horror to impel me to write another of my pointless reports on books. That dishonor belongs to the passage quoted above, wherein our British former secret service agent and therefore (in the logic of such books) expert in the King’s English utterly misuses the word ‘chary’. I stumbled over this passage and tried in vain for some time to ascertain just what word the author thought she was using; I finally had to confess my ignorance. (Hairy? Harried? Scary?) So for this final felonious assault upon the very language itself, I charge The Lies That Bind with its multitude of crimes and plead that it be consigned to the dark donjon of unworthy books.

However, such a fate is not to be. Not only has Kate Carlisle met with success with her Brooklyn the bookbinder series of ‘mystery’ novels, she has foisted another improbably named character upon the unwary world in the Shannon Hammer ‘Fixer-Upper Mysteries’. Set in the fictional town of Lighthouse Cove, California (which is consciously modeled as a West Coast variant of Miss Fletcher’s Cabot Cove), that new series has already seen eight books and three Hallmark Channel movies. And the ‘Bibliophile Mysteries’? We’ve been discussing book number three, and number fourteen was published only last June. Putting both series together, that means 2.2 books per year for the past decade. Oh, and Ms. Carlisle has already contracted to deliver at least two more books in each series. Well, as I say often about myself, “If I’m so smart, how come …”

Ta-ta.