NOTE: Due to recently (5 July 2018) discovered errors in underlying data, some statements in this post are incorrect. The original post is preserved, with new corrected information presented in monospace font. More information can be found in this blog post.

As I just mentioned, I recently finished reading 200 books, counting from when I commenced recording such information in my books database back in June of 2015. Herewith I present some findings of no ultimate interest, derived from an analysis of the underlying data found in that database. We will be considering the last hundred books (i.e., books #101 – #200) read, where books in the “Comics & Graphic Novel” category do not count towards that total.

The first stat is that already given in the original notification of my 200th book read, which is the fact that I took — on average — just under six-and-a-quarter days to read each volume. This compares with 4.83 days per book read for the first one hundred. (Incidentally, the total average for reading the complete 200 books becomes slightly over 5-and-1/2 days per book. Put another way, three years and ten days were required to read the total set.)

1 Book per 6.24 Days

1 Book per 6.17 Days

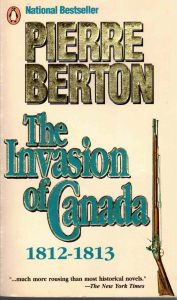

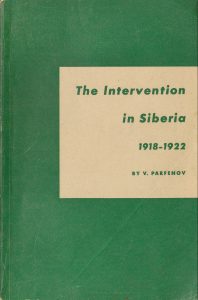

I am surprised to discover that my ‘comfort food’ reading (discussed in my report on the first 100 books) had subsided somewhat. Whereas the last report showed a 3-to-1 ratio of fiction (of all types) to nonfiction works, now the ratio is 4-to-3, with History books dominating the nonfiction ‘category’. (The Categorizing Imperative is its own fraught issue, one perhaps worthy of discussion another time.) Specifically, 57 books were some type of fiction, leaving 43 nonfiction works. Once again, mysteries dominated the fictional works, with the actual breakdown as given below:

Books Read by Genre

| Mystery |

30 |

| Fiction |

13 |

| SF & Fantasy |

14 |

| Nonfiction |

29 |

| History |

14 |

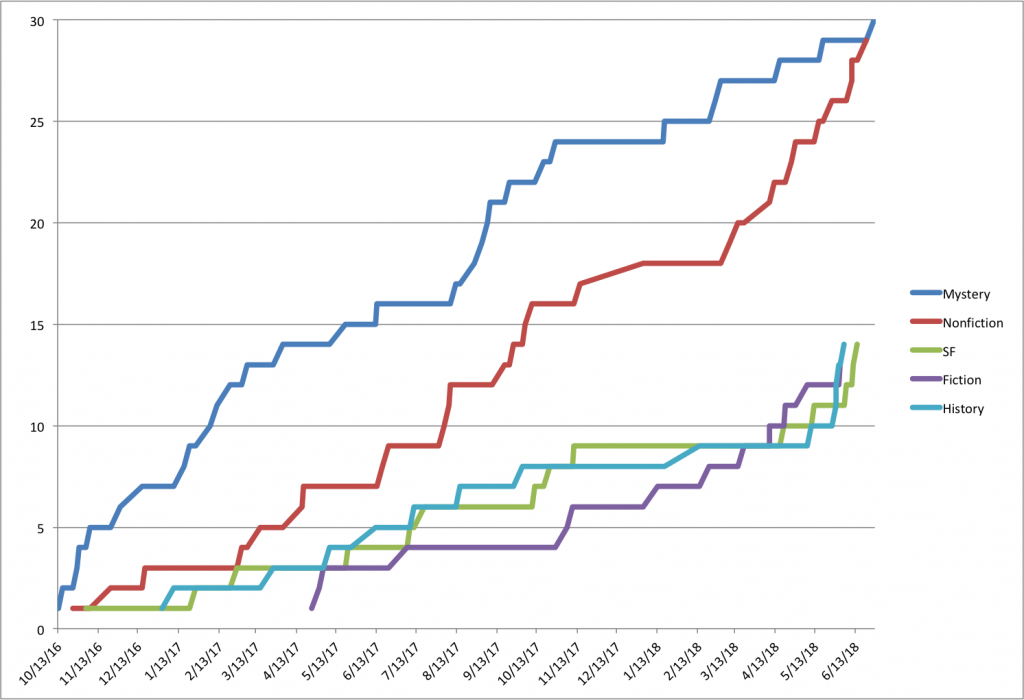

All category information remains unchanged from the initial report, as the previously unrecorded book belonged to the Mystery category and the quondam 200th volume (now #201) belonged to the same genre. Thus the table above and the chart below are still valid, along with any other information based upon categories, save for the time series chart below the Nonfiction breakdown (q.v.).

Or, for those who prefer charts…

Nonfiction, of course, is a term covering up any number of sins. Excepting the fourteen History tomes read, the complete breakdown of nonfiction books in this last hundred is as follows:

Nonfiction Breakdown

| Children’s Books |

2 |

| Film |

2 |

| Indians of North America |

1 |

| Militaria |

1 |

| Mythology & Folklore |

2 |

| Philosophy |

4 |

| Poetry, Drama, & Criticism |

6 |

| Psychology |

1 |

| Religion & Spirituality |

5 |

| Science & Math |

3 |

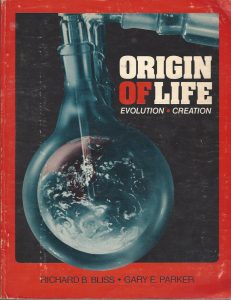

| Wacko |

2 |

Apparently I was getting real literary in my reading lately…. I’ll also note here that I read 7 books in the Comics category, not included in the count towards 200.

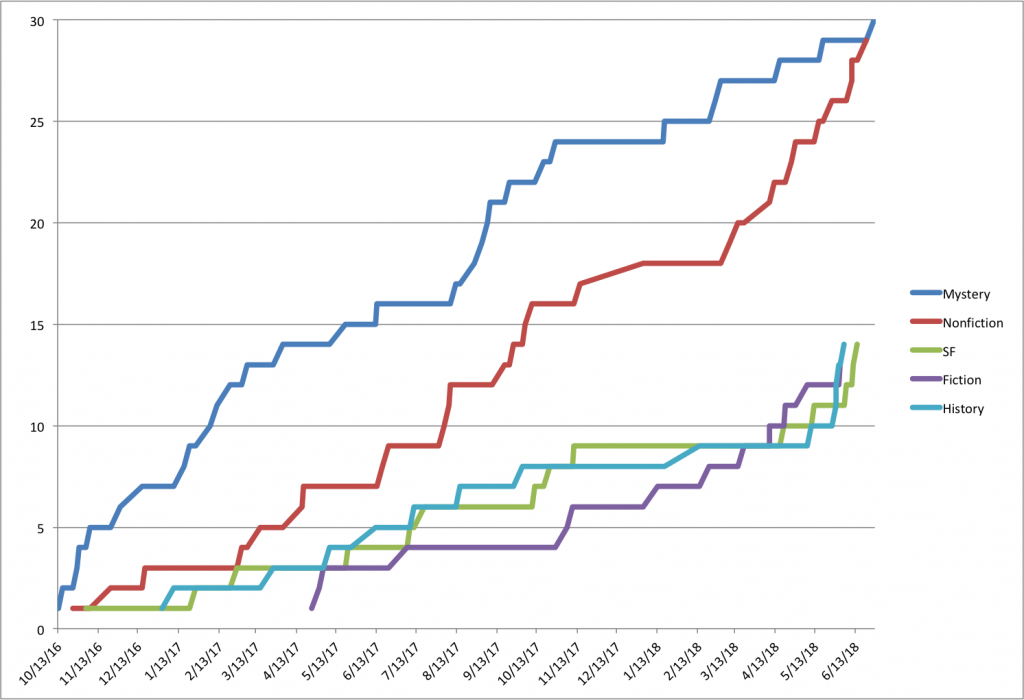

As I did in my last report, I present a time series chart showing when these books were read, broken down by genre.

I have not bothered to update this chart — because I do not care to. If you really care (and we both know you don’t), just imagine an uptick of one book in the mystery line on February 1, 2017, with a concomitant reduction at the tail end of that series line.

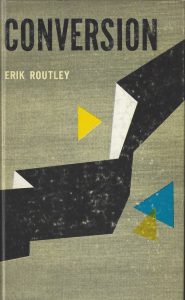

Speaking of time, the earlier six-and-a-quarter days per book is, of course, an average. Reviewing the data I found that there were some periods where much more time passed between completed books. Several books were finished more than ten days after the previous volume, and in two instances more than twenty-five days passed between successive books. The greatest time between books occurred when I was unable to maintain anything like a steady reading pace during the last Christmas season, and forty-eight days passed between the completion of Conversion by Erik Routley (finished November 15, 2017) and Fallacies and Pitfalls of Language: The Language Trap by S. Morris Engel (completed on January 2, 2018). As an aside, I’ll say that I cannot recommend the first slim volume by Routley enough (or anything by the hymnology expert).

there were some periods where much more time passed between completed books. Several books were finished more than ten days after the previous volume, and in two instances more than twenty-five days passed between successive books. The greatest time between books occurred when I was unable to maintain anything like a steady reading pace during the last Christmas season, and forty-eight days passed between the completion of Conversion by Erik Routley (finished November 15, 2017) and Fallacies and Pitfalls of Language: The Language Trap by S. Morris Engel (completed on January 2, 2018). As an aside, I’ll say that I cannot recommend the first slim volume by Routley enough (or anything by the hymnology expert).

Of course, the date I finish a book often has very little relation to the time the book was started. Indeed, there are any number of books by my bedside that have been started and restarted, with varying degrees of progress made within. I have thought of tracking the date I first commence reading a book, but have decided that that way lies madness — or, if I have already crossed that threshold, even deeper insanity.

I generally decline to comment on the relative merits of the books I read, though I’m happy to give recommendations if you want them. I don’t like everything I read, and indeed this last hundred had a few stinkers among them. I do rate the books on a 5-star scale, though I have yet to find something so execrable that it deserves a single star. Thus a perfect mean across all books would be 3.5 stars if an equal number of possible ratings were given. This last batch of a hundred books had an average rating of 3.9, which is pretty good, but has dropped from the average rating for the first hundred, which was exactly 4*. (*for books actually rated. Not all books were rated when I first started tracking my reading. And while I’m in this parenthetical note, I will point out that these ratings include the comics I read, though there was little change due to those (The last hundred, for example, has a total average rating of 3.89 for all books, and a average rating of 3.87 if the comics are excluded.).).

among them. I do rate the books on a 5-star scale, though I have yet to find something so execrable that it deserves a single star. Thus a perfect mean across all books would be 3.5 stars if an equal number of possible ratings were given. This last batch of a hundred books had an average rating of 3.9, which is pretty good, but has dropped from the average rating for the first hundred, which was exactly 4*. (*for books actually rated. Not all books were rated when I first started tracking my reading. And while I’m in this parenthetical note, I will point out that these ratings include the comics I read, though there was little change due to those (The last hundred, for example, has a total average rating of 3.89 for all books, and a average rating of 3.87 if the comics are excluded.).).

Average Rating for Books Read: 3.9 Stars

Average rating info also did not change, as the rating for the missing volume was identical with the volume ‘forced out’ by becoming #201.

Another change to my record-keeping has been the addition of page counts for each book entered. This was begun during the last hundred, so the records are as yet incomplete, but over 90% (including comics) of these books do have this datapoint, so I can state that the average book length (using those books with that data for the calculation, with the error that implies) was 226 pages, or 236 pages if comics are excluded. My total page consumption (including comics, again) was north of 21,990 pages. We’ll check back in after the next tranche with (one hopes) more complete data.

Average Book Length: 236 Pages

Changes based upon page count data are purely nominal, as the missing book which replaced the former #200 had only 7 more pages than the latter. Thus the average page count increased by only 8 hundredths of a page.

I will return in the near future with the complete list of books read.