Recently I read yet another statement decrying religion, blaming religion for most of the assorted atrocities and ills of mankind. It did not help that the quote was attributed to Bill Maher, who has the tactful subtlety of pancreatitis, nor that the person promulgating same was someone I respect very much, and whose good opinion I crave. I could not reign myself in, however, and gave vent to a contrarian view, as is my wont. After some back and forth I realized that my negative reaction to such generalized statements as ‘religion causes harm’ could not be summed up in a few sentences, so I am trying here to briefly sketch out why I think such arguments are glib and facile.

When reading that most human horrors — wars, bigotry, repression, torture — can be blamed primarily upon religion, I am saddened. I can see some justification for the claim, and long indeed is the list of crimes and terror committed in the name of this or that religious belief. But I believe that something is lost, something of great value, if we permanently consign religion to society’s dungheap. For one thing, we negate almost all human actions which occurred more than two centuries in the past. Homo saecularis is a quintessentially modern being, ushered in to our present world by the unholy trinity of Darwin, Marx, and Freud. And though only the former gets a sticker on the back of cars, all three can be said to have heaped their shovel full of mere earth upon the grave of God. But I believe we lose not only our past experience by an unthinking negation of religion as a whole; I think that we run the risk of cutting ourselves off from an essentially human experience, that we negate a fundamental force in society, if we declare that religion to be useless as a whole.

To be sure, I must first define my terms, for I do not view religion as this or that set of beliefs. I follow more of Durkheim’s model, and am not entirely sure that society is possible without religion. To my mind, convicting religion for human murder is as apropos as blaming oxygen for the same felonious acts, as both have been present wherever humans have existed; there even may be — perhaps! — correlation, but causality remains to be proven. In Durkheim’s construction, human beings gather together for corporate events and experience the power of their mutual activity, which he calls mana. Seeking to replicate that feeling and power, people repeat the rituals, eventually codifying and organizing the activities and beliefs around them. This organized specification defines the areas of the sacred and profane, and thus religion is a projection of society itself upon the universe in which this group of humans find themselves. Durkheim’s approach posits that every society will have some religion, and proceeds from his fundamental principle that “the unanimous sentiment of the believers of all times cannot be purely illusory.”[1] Now this of course will raise howls of objections — for one thing, each religion teaches completely different beliefs, and there is no unanimity to be found. But Durkheim is speaking of the universality of religious experience, not the trappings within which it appears wrapped.

Seen in this light, Durkheim shows just how helpful religion has been to humanity, a fact entirely lost upon the Bill Mahers of the world. I do not mean by this the positive accidents of religions which can be counterpoised to the terrors mentioned at the onset: the preservation of knowledge, the sense of purpose and meaning given to millions, the structures which have supported good causes and actions. No, Durkheim here is talking about the most basic supports of our human reason, classification systems which we now take for granted, so prevalent have they become. Such notions as the idea of time itself, with its hours, days, weeks, months, and years, or even concepts of space, force, personality — all these have their roots in the religious consciousness.[2] In fact, the very idea of the ideal — which fuels the atheistic attacks upon religion — stems from religion, for it is religion that explains man’s propensity for thinking of and striving for a better ‘other’, whether in this world or the next. As Durkheim says,

our definition of the sacred is that it is something added to and above the real: now the ideal answers to the same definition; we cannot explain one without explaining the other. In fact, we have seen that if collective life awakens religious thought on reaching a certain degree of intensity, it is because it brings about a state of effervescence which changes the conditions of psychic activity. Vital energies are over-excited, passions more active, sensations stronger; there are even some which are produced only at this moment. A man does not recognize himself; he feels himself transformed and consequently he transforms the environment which surrounds him. In order to account for the very particular impressions which he receives, he attributes to the things with which he is in most direct contact properties which they have not, exceptional powers and virtues which the objects of every-day experience do not possess. In a word, above the real world where his profane life passes he has placed another which, in one sense, does not exist except in thought, but to which he attributes a higher sort of dignity than to the first. Thus, from a double point of view it is an ideal world.[3]

Now this power of idealization is behind such thoughts as “Wouldn’t the world be better if only there were no religions?” Only the religious impulse can bring about the positive action to create this heaven on earth, which may be anathema to most atheists.[4] But is atheism not itself religious? Well, there may be some Pure Land Atheists who are beyond such trivial concerns, but… Two points occur. Firstly, much of glib atheistic belief seems to fit the (non-Durkheim) mode of religious belief, wherein the subject 1) has an insight which cannot be proven scientifically, and then 2) is impelled to convince others of its truth. Thus proselytizing disbelief fits William S. Burroughs’s ‘language is a virus’ definition of religion. Secondly, the idea of condemning others for not being right-thinkers, of ascribing to non-non-believers every sort of foul act, prejudice, and excrescence imaginable also seems very religious in the non-formal and perjorative sense. It seems almost to be just what some are complaining about in other religions, in fact.

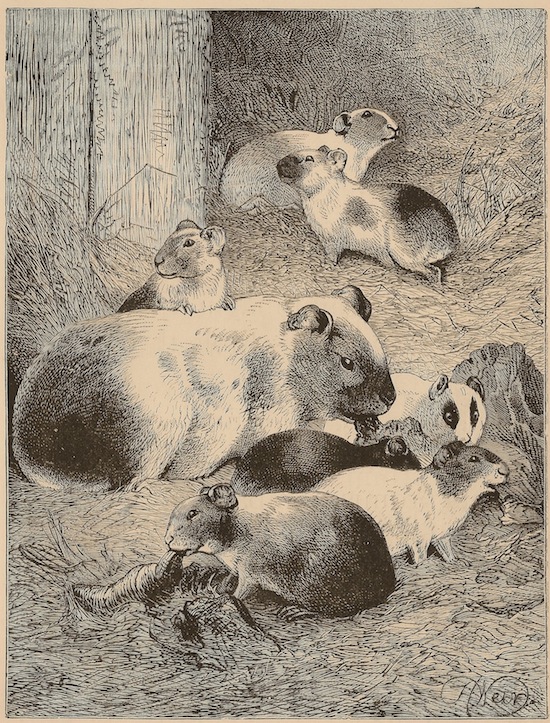

Thus according to my construction, religion is something we are stuck with, whether it be the product of weekly church visits from birth or yearly pilgrimages in costume to Comic-Con or Burning Man. If we want, however, to say that this religion or that religion is bad, I suppose one can make those arguments, and I will listen. I am not a moral relativist, believing that all societies are fundamentally equivalent (Don’t get me started on Bronies). There are also similarities among true atrocities which should be examined, and studied thoroughly. One of these is the idea of committing acts ‘In the Name of _____’; this is where the 3rd Commandment’s proscription could help, I believe.[5] But the biggest contributor to horror seems to me not to be religion per se, but the continual struggle of ‘Us’ versus ‘Them’. Defining the ‘Other’ as anathema, subhuman, worthy only of contempt — this to me seems to be the root of so much terror and death. Was the murder of the Jews by the Nazis religiously based? If so, does that mean that Anti-Semitism is a religion? But I admit I do not know the answer to the fundamental questions raised by the terrors of the 20th Century.

I do feel strongly, however, that if we are content to blame religion of all, or even most, hateful atrocities, we abdicate responsibility for these same acts. Not that “we all killed the Kennedys”, but that we risk losing sight of the complex social interactions that lie behind most of the crimes most often credited to the malevolent influence of religion. The majority of the witch burnings, for example, turn out to have occurred in European domains where weak rulers followed popular accusations with strident executions to prove their mettle, as it were. In demesnes where rulers were strong, on the other hand, original accusations of witchery were not allowed to spiral into further cycles of accusations, and often the penalties were exile rather than death.[6] We also know that the majority of the witch trials followed the Protestant Reformation, rather than the medieval Inquisition, strangely enough. I suggest only that a more nuanced view of these and other hateful occurrences is necessary if we are to ever truly understand their causes and, one hopes, the ways they may be prevented. The facile assignment of blame to religion blinds us to the complexity of social life that may hold the key for understanding these and other acts of the human animal. As Francis Bacon (the old one) said,

for as God uses the help of our reason to illuminate us, so should we turn it every way, that we may be more capable of understanding His mysteries; provided only that the mind be enlarged, according to its capacity, to the grandeur of the mysteries, and not the mysteries contracted to the narrowness of the mind.

1Emile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life, trans. Joseph Ward Swain (The Free Press: New York, 1965), p. 464.

2Durkheim, op. cit., pp. 22-25.

3Ibid., pp. 469-470.

4This is similar to the old canard that anarchists would be a real threat if they could ever get organized.

5I also love Leonard Cohen’s line “You say I took the name in vain/Well, I don’t even know the name.”

3William Monter, “Witch Trials in Continental Europe 1560-1660”, in Witchcraft and Magic in Europe: The Period of the Witch Trials, ed. Bengt Ankarloo (Philadephia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002), pp. 12-17.