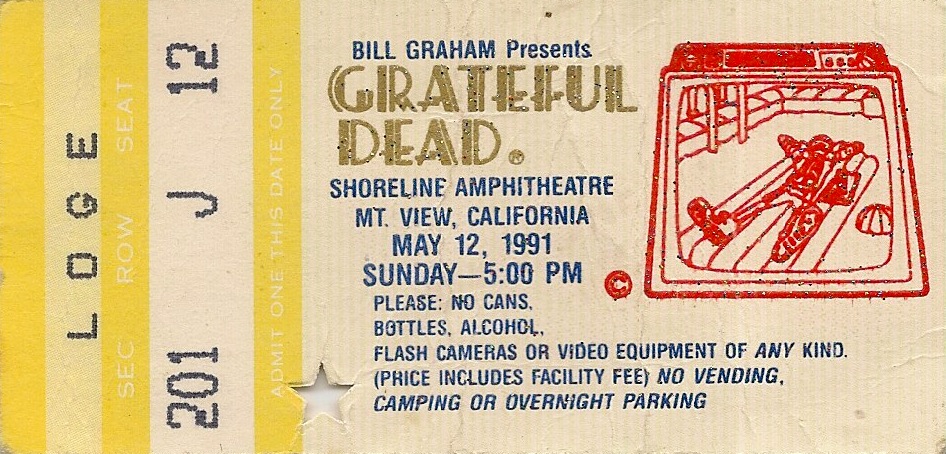

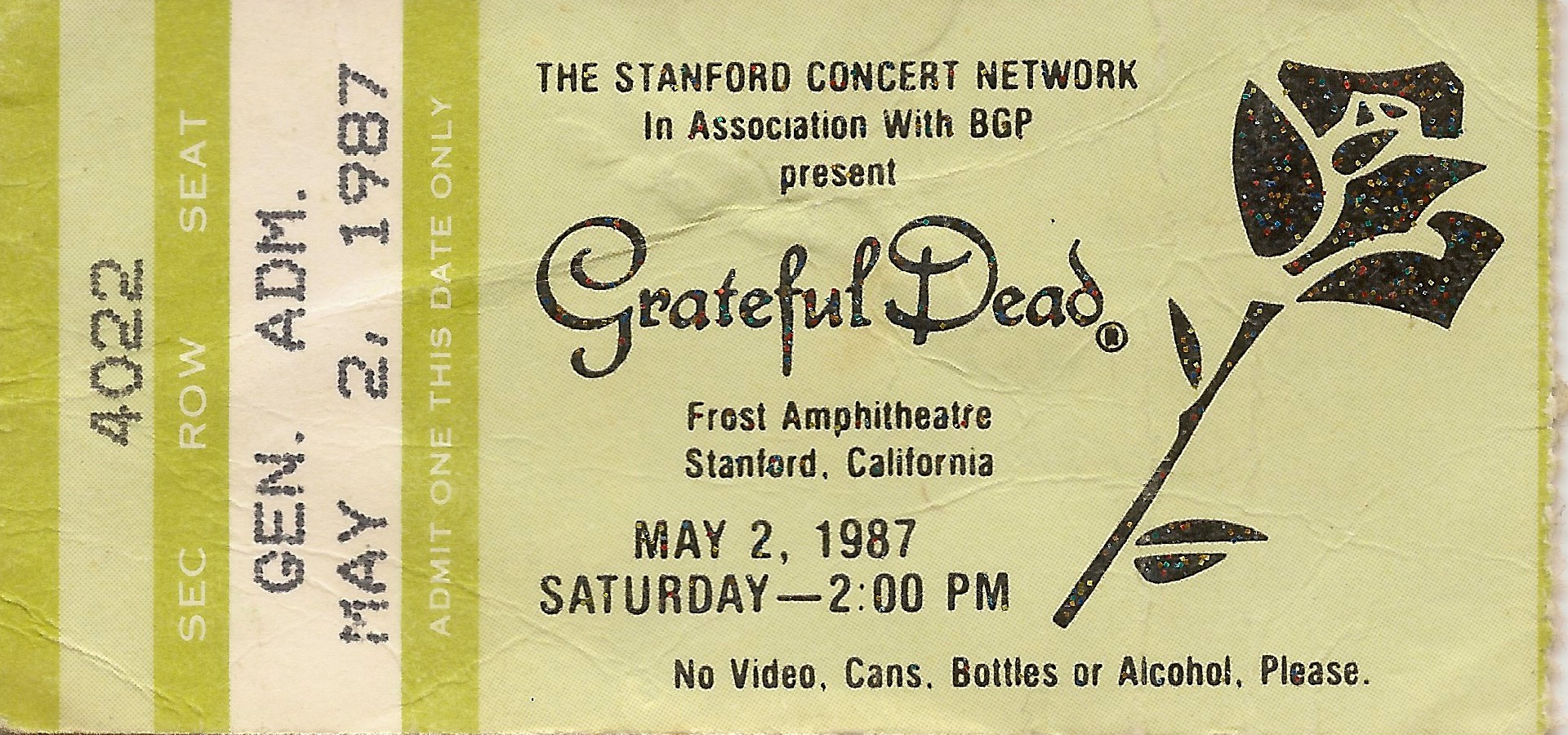

Almost certainly one of my first — if not the first — Dead shows… And what a wonderful venue for communion with Garcia, 32 years ago today.

And then…

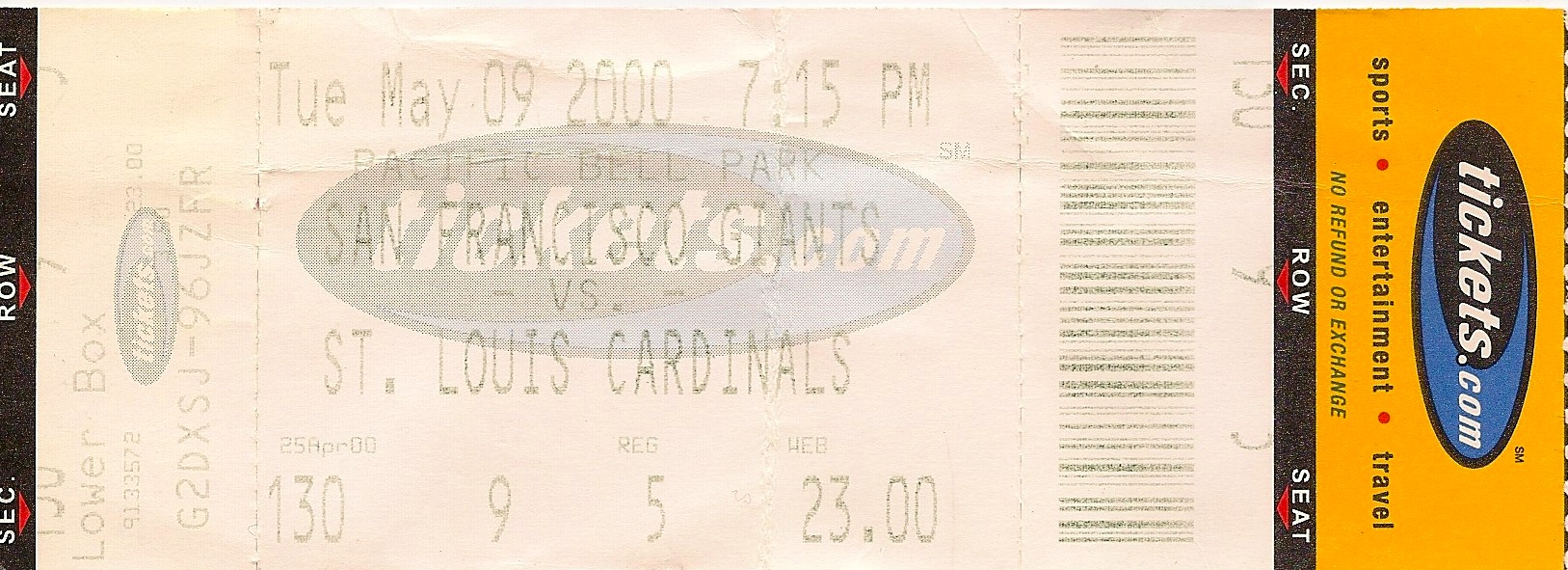

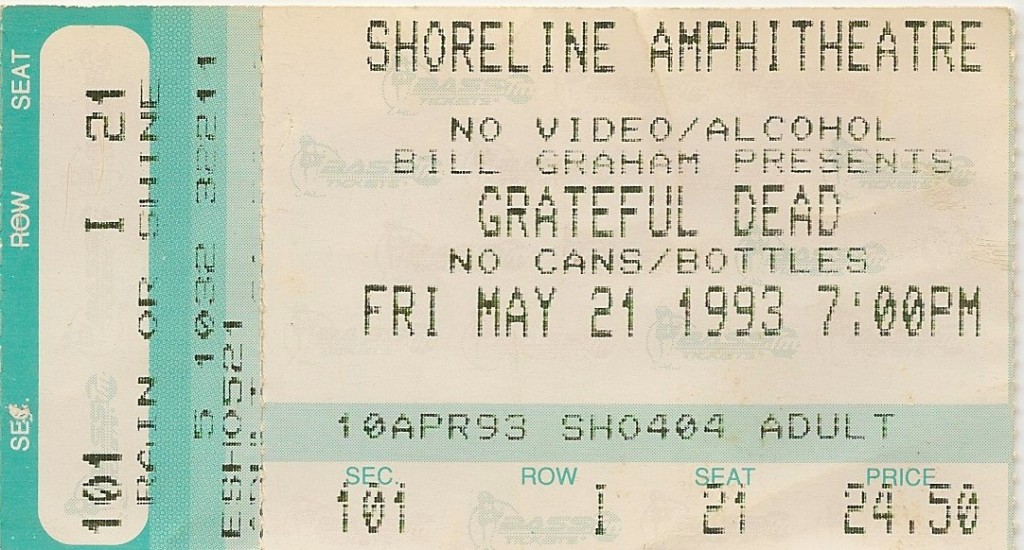

21 years ago, a different show, a different outdoor amphitheatre, same Dead, same Deadheads, different me…