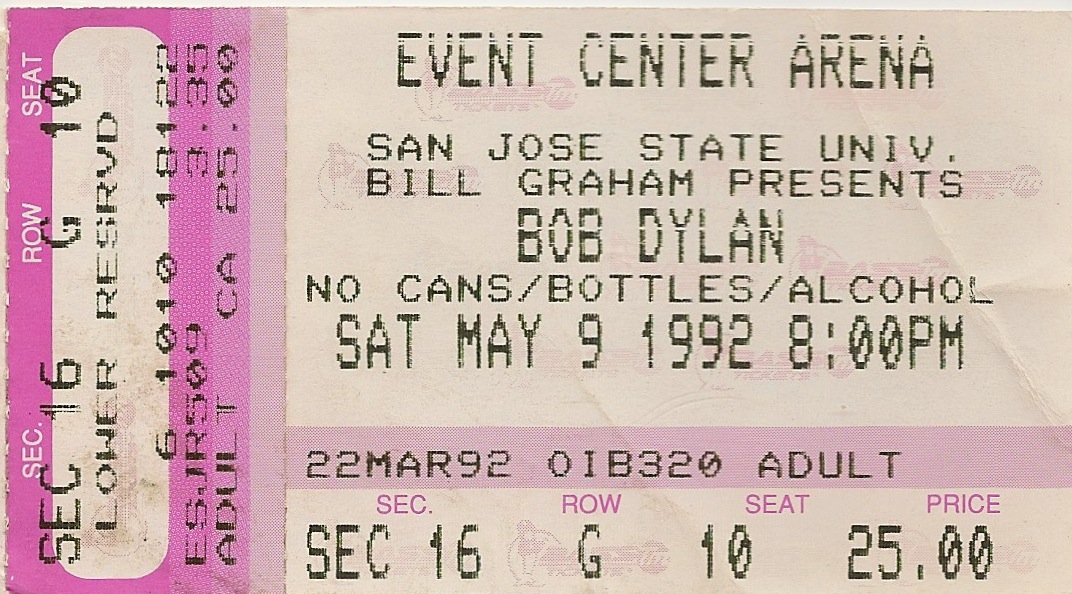

19 years ago Dylan was amazing, and the Warfield was a magical place. Something funny happened the next night, but that’s for another day…

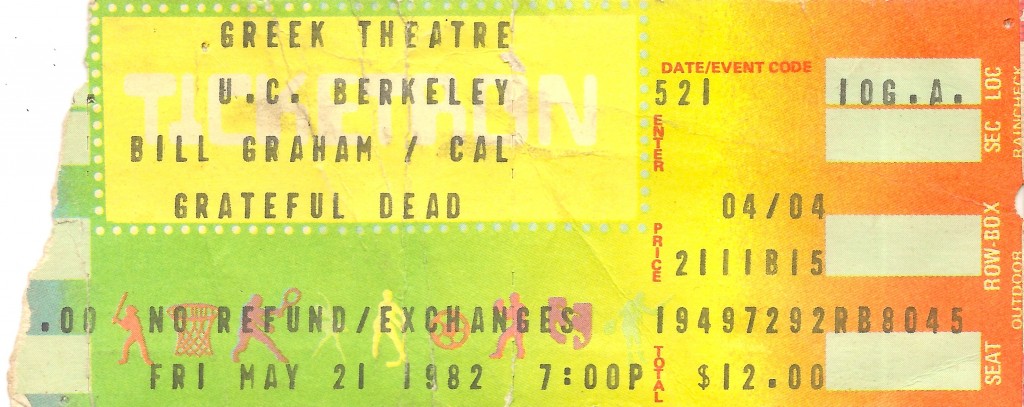

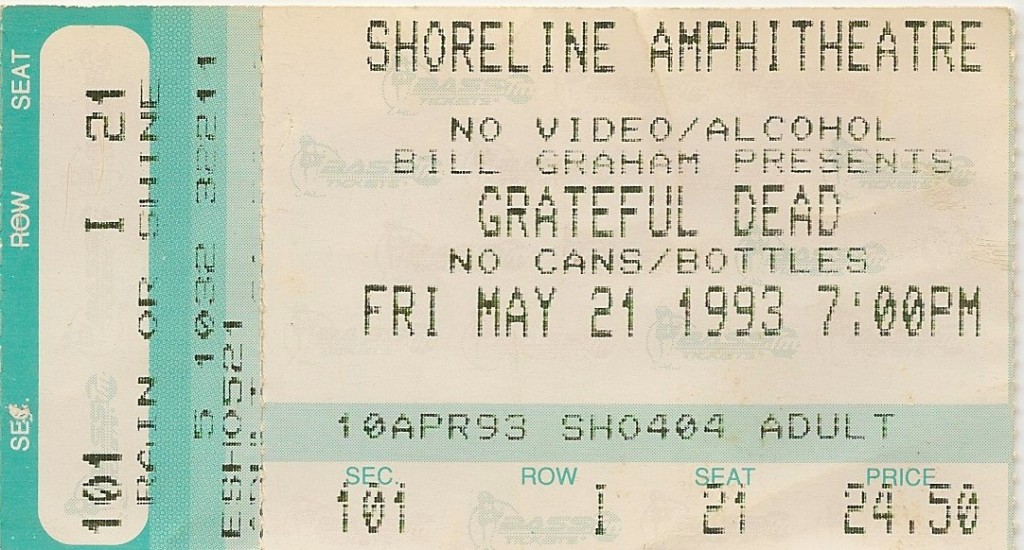

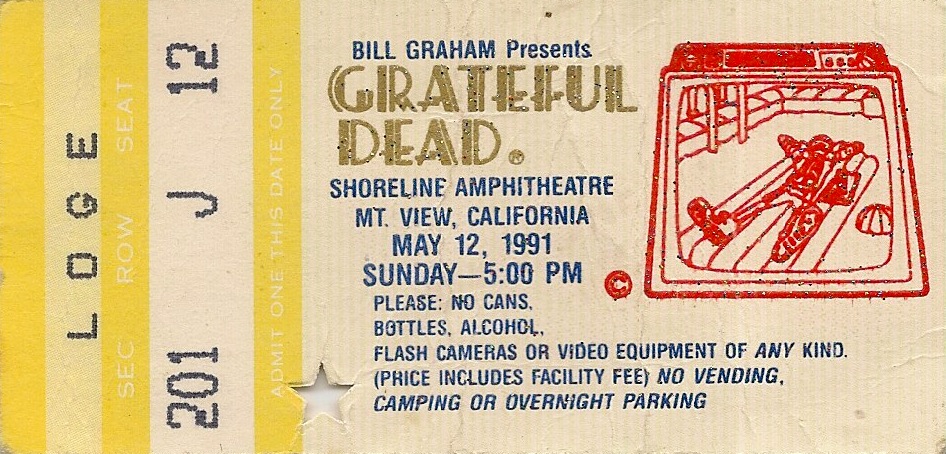

The Deadheads Turn Their Buds To Shake In May

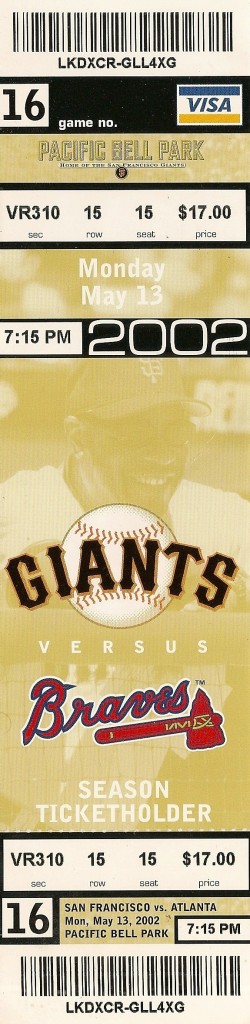

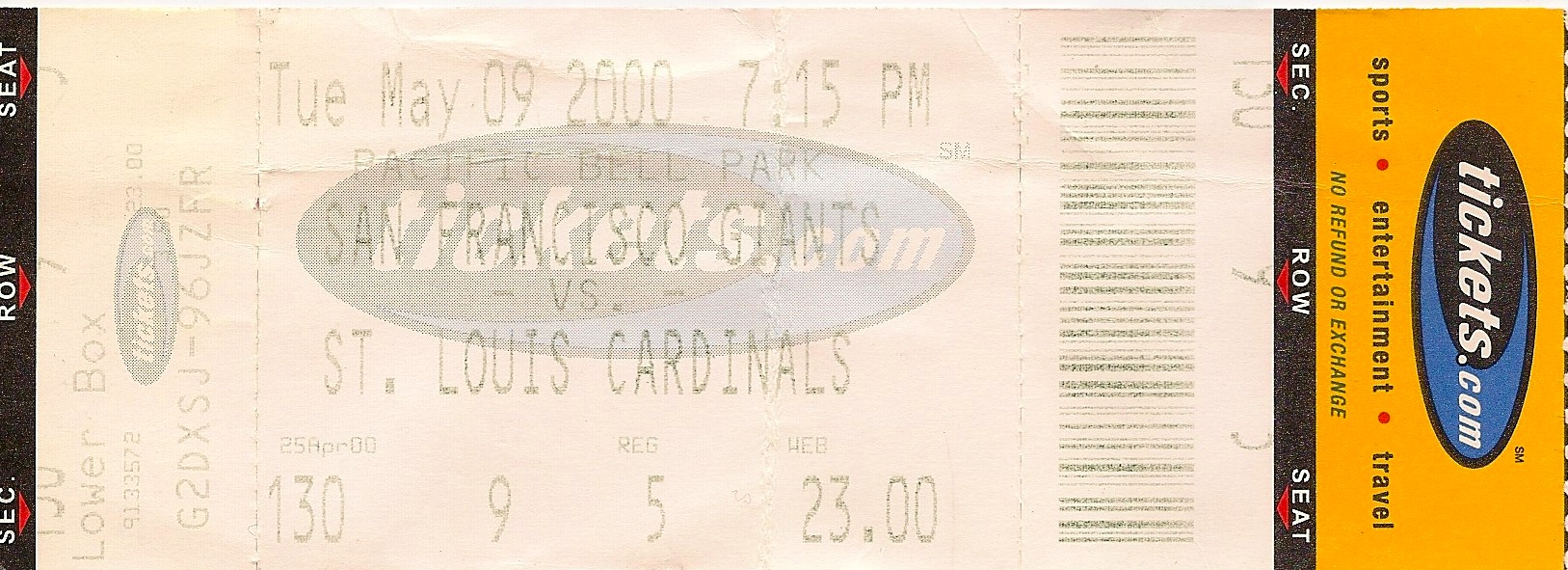

Do the Giants Always Beat The Braves?*

Looks like I watched the Braves in a losing effort as the SF Giants managed to win it in the 11th after the Braves came back in the 9th to tie the game at 6 all.

I’ve managed to suppress all memory of the game…

Atlanta Braves 6 – SF Giants 7

More May Tickets Madness: Dead

Hannah’s First Baseball Game

In a losing effort, Hannah and I cheered on the Braves (well, the 3 year-old girl sometimes cheered for the wrong team…) on this date 15 years ago. It was Barry Bonds ball night (BOO!!!), and I still have the ball, never having had the chance to throw it at an appropriate person.

SF Giants 4 – Atl Braves 1