I Read It So You Don’t Have To Dept.

The Banality of Feeble Dept.

Journey To The Impossible: Designing an Extraordinary Life, by Scott Jeffrey

This is perhaps the worst book I have ever read in my life.

I was sorely tempted just to let the above sentence be my entire report upon this piece of garbage, much as the original version of a sophomoric poem I wrote to entertain my fans in high school once consisted of only the words: “Dead. Damn.” However, a somewhat decent respect to the opinions of others compels me to provide proofs of my assertion, lest you too end up poleaxed by the pure inanity of this so-called book. Socrates credited his daimonion with warning him often, and the Roman genius later became a similar ‘divine something’ which looks over and after a person in their journey through life. But neither ‘genius’ nor ‘demon’, nor ‘angel’ nor ‘devil’, no divine force nor powerful spirit drives this work of trash into the ground of senseless, useless self-help experiential ‘up yourself’ crap-claptrap stream of unconsciousness and extreme Dunning-Kruger diseased and morbid stupid. No, the ‘force’—if such it can be called—behind this saddening refuse can only be all too human, alas, so very human, in the sense which makes us neither gods nor beasts, but in some way much, much worse than either. An insensate lack of self-awareness in the midst of professing powers of self beyond normal ken permeates the 200 pages (thankfully with wide margins and wide line spacing, typeset by someone who knew how to pad that essay into the required length for the professor) of this terrible, terrible example of English words placed upon paper.

Hmm. I’ve already said much more about this book than it deserves, so let me make the basic case quickly, and then give you an extended extract to show you what I am gassing on about.

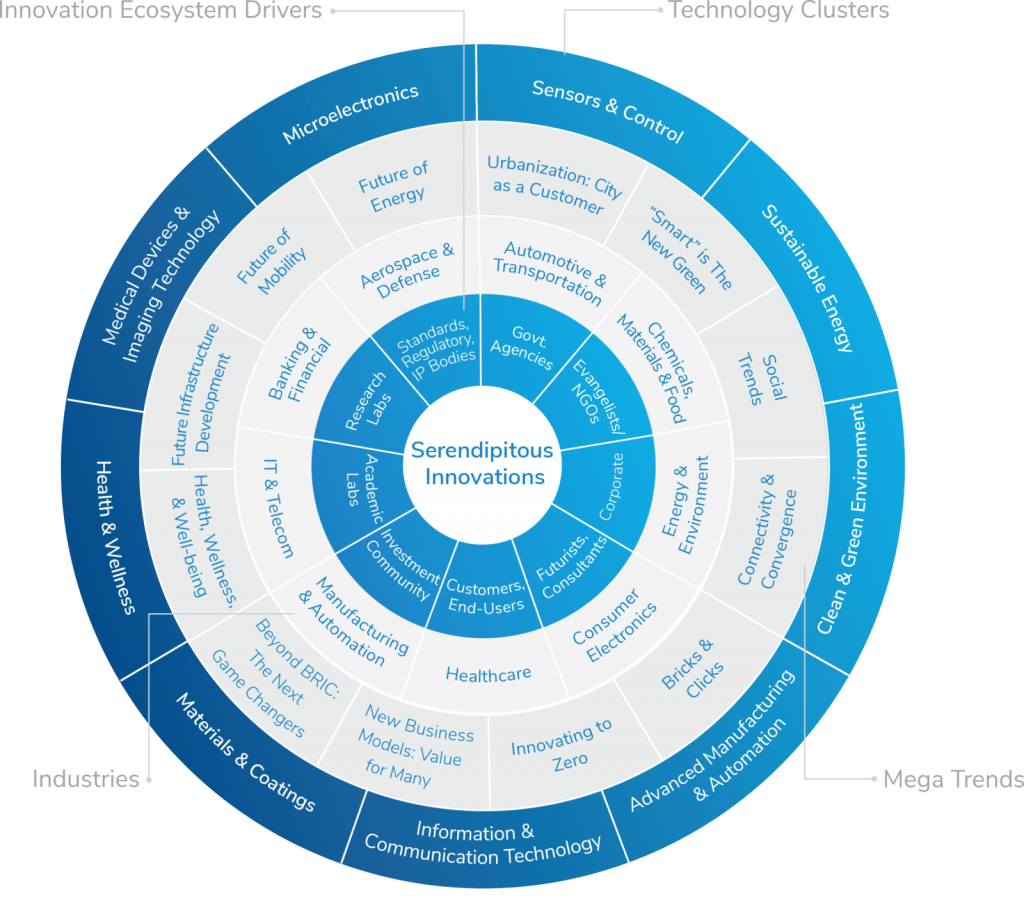

Mr. Jeffrey’s Journey To The Impossible is only the worst example of the corporate meaningless speech that once was kept in its place at the yearly (or at worst quarterly) company meeting where the ‘leadership team’ performed their leadership act for the rank-and-file. At some point in the past twenty years, however, executives in every organization became convinced that speaking the buzziest of words and mouthing the most clichéd business platitudes what what being an executive was all about. Indeed, entire companies were founded around this supposed skill, devoted to helping other executive types uncover such nebulous items as ‘actionable intelligence’. A case in point:

Such meaningless nonsense abounds all over the Web, in the soi-disant ‘Tech’ industry, in boardrooms and country club locker rooms. The example I show here is only one of hundreds, perhaps only more successful up to this point than most. If you go to this company’s website, you’ll find more of this ilk, including this fabulous ‘Convergence Expertise’ Wheel of Bullshit:

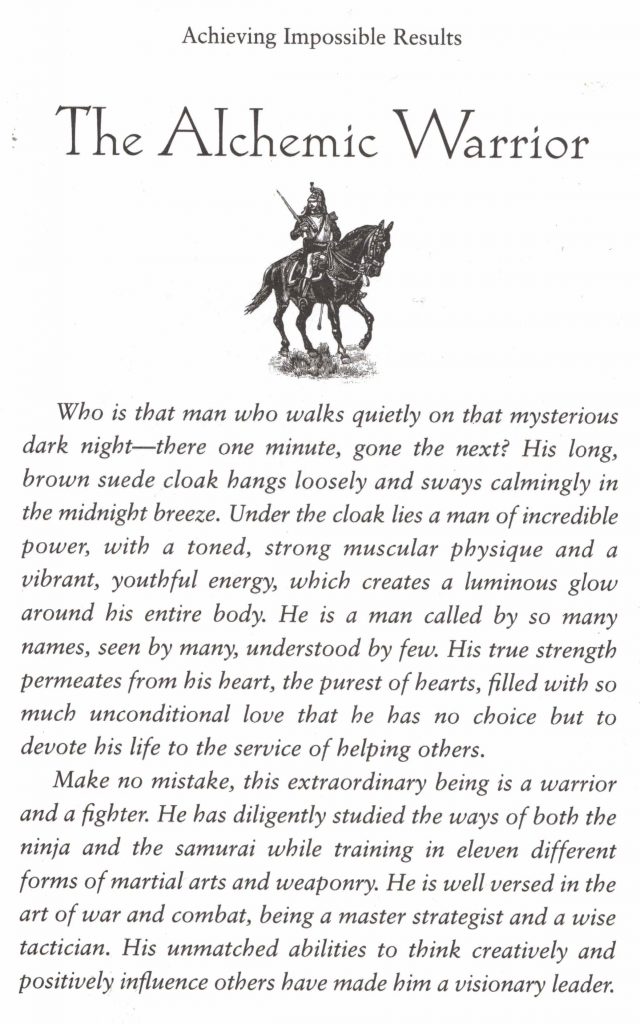

Scott Jeffrey made his mark as one of the self-actualizing gurus to this executive suite, trying to sell them his brand of Babel in a crowded marketplace of similar Kool-Aid. This book is the distillation of his lessons learned as he—wait for it—journeyed to the impossible. The lessons are as you’d expect: Nothing Is Impossible, Be The Best You You Can Be, Be Creative, so forth and so on. I will now give you just a small sample of the ideas for ‘designing an extraordinary life’ that are contained in this book. What follows is an extract of Mr. Jeffrey’s idea for writing a bio for the ‘lead role’ in your life, based on his personal experience doing just that for himself. He worked and pulled together “a fantastic character that got me juiced …. I didn’t take myself too seriously, there was no judgment, and I was proud of what I had created.” I can easily believe he used no judgment, but here, you can judge for yourself:

But wait, we’re not done yet ….

This is so sad on so very many levels. One of the reasons I can identify losers is because I can identify with them, have been and are a loser. Which means that I’ve played D&D and related games wherein slobs like me sit around with weirdly shaped dice and pencils and sheets of paper pretending to be a misogynistic half-breed elven communist mage wielding a magic custard pie with deadly accuracy. Only the misogyny had any basis in reality. I mention this only to say that I have ‘rolled’ many characters in such pursuits, have seen many other characters ‘rolled’, and I have never seen, heard, or imagined a more banal, more buffoonish, cartoonish, and pointless character biography than the passage quoted above. And one of my ‘characters’ had a pet bear with constant intestinal distress, named Wambler.

Scott Jeffrey still runs a business consulting firm, or rather, a “transformational leadership agency and resource for self-actualizing individuals read by over 2 million people”. He still has not hired a copyeditor, though Journey To The Impossible had good production values, which is perhaps the biggest difference in the current After Times; where once we could detect the Crazy by the blurry mimeograph streaks on the crumpled pages stapled lovingly to telephone poles around campus, now even the stupidest of ideas are shiny and chrome.

There is a lot more to hate in this book. Heck, I’ll send it to you if you want to see how much worse it can get. Mr. Jeffrey wrote this appalling waste of time and ink over 18 years ago, using a author portrait that makes him look like Kahlil Gibran in a turtleneck.

He grew older, however, as did we all, and now reminds me more of the (fictional) author of The Profit, which is a much better book than Mr. Jeffrey’s, and is even shorter. Maybe we’ll read that one next time.